Evolving Practice

War and Politics

Portraits

German Sublime Tradition

Social Issues – Travellers

Religion

Prostitution

Sites of Sexuality

War and Politics

Patrick Hennessy’s return to Ireland in late 1939 was part of a European exodus that included Irish artists like Louis le Brocquy and an influx of foreigners like the White Stag group led by Basil Rákóczi and Kenneth Hall with Stephen Gilbert, Jocelyn Chewett and many others. The period of the Second World War was known as The Emergency in neutral Ireland. It is imagined as a closed and bleak time, but Bruce Arnold has pointed out that the presence of so many painters, poets, writers and musicians made the cultural climate attractive and exciting. It was less isolated than history has made it and diplomatically there was a degree of turmoil and excitement as spies and agents moved among the citizens. Importantly he notes that ‘in a Europe dominated by Fascism, Ireland was ‘free’.

Hennessy responded to this unique climate in a number of diverse ways. In works such as Exiles and De Profundis, we see the human or his simulacrum placed within blasted, post-apocalyptic landscapes. In the context of the war during which they were created the narratives contained within these works seem somewhat self-evident: man has created this catastrophe and these images depict the result of his folly. In De Profundis, Trinity College is depicted in ruins. Trinity was traditionally a Unionist institution. Imagining it in ruins can represent the collapse of British influence in Ireland. In his letter to Alex Allen Hennessy notes how during The Emergency, ‘a few silly students in Trinity College threw the patriots into a frenzy by burning the Irish flag. Bands of elderly ladies marched to and fro with banners and such like, and after a deal of speechifying burnt a home-made Union Jack.’

In several other works, Hennessy paints pictures of the Big Houses of the ascendency that had been burned down in the troubles. De Profundis complicates this historical animosity between ‘English vs Irish’. It is a reflection on a new ‘enemy’ on Irish territory. The traditional British foe has been replaced by the Germans, who had ‘accidentally’ bombed Dublin in 1940 and ‘41. Hennessy had noted some anti-British / pro-German sentiment in Ireland during the Emergency, what he calls ‘die-hard Nazi sympathisers’. Thirty years before, Dublin had been shelled by British forces during the 1916 Rising. Hennessy’s imagining of future bombing in 1944 by the Germans can be read as a warning to those people who were their putative allies. This work has usually been reviewed using the language of Surrealism and indeed when these images are considered ‘surreal’ then their bleak other-worldliness give them the clarity and strangeness of a dream remembered. However Hennessy’s other, most iconic work made during the war, Exiles in the collection of Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, could be read as a statement of fact rather than a work of the imagination. It could fit into the canon of official war art.

Dublin-born Sir William Orpen (1878-1931) was made an official war artist during the First World War in 1917. His important work Zonnebeke, now in the Tate Collection was painted in 1918 following the Passchendaele campaign in which half a million lives were lost for the sake of a five-mile advance. Zonnebeke forms a point of comparison to Exiles in a number of ways. The palette is very similar being restricted to dun browns and greys with a flash of blue.

The storm clouds overhead are dark enough to suggest smoke rather than rain. Both figures wear army fatigues. Water flows away from the central figure in a serpentine composition and strikingly the broken column in the Hennessy picture finds its counterpart in the blasted tree-trunk in Orpen’s work. There had been unseasonable rain in August 1917 that turned the soil of Flanders into a sea of mud. Wyndham Lewis described it as ‘a new unchartered ocean’ and describing Zoonebeke as a sea became a feature of many wartime memoirs. It is a poignant fact that Hennessy’s father John, a sergeant-major in the Leinster Regiment, was killed at Passchendaele in 1917 so these and other works from the First World War would have had special resonance for Patrick. One can imagine this as a self-portrait while the figure in the distance is his mother Bridget looking out to where she had lost her husband – the father that Hennessy never knew. It is the Hennessy family that are the eponymous Exiles. After John Hennessy’s death, Bridget remarried a Scotch officer who had been stationed in Ireland with the Black and Tans. Certainly they would have found the new state unwelcoming so Bridget and her second husband took her six children [of whom Patrick was the youngest] to live in Arbroath, Scotland. As pointed out by Kevin Rutledge, Hennessy did not remember his time in Scotland happily and looked forward to returning to Ireland where he could make a fresh start and build a new life.

In 1943 when Exiles was painted, the Germans had not yet turned east to face the Russians – that major turning point in their fortunes – and it must have seemed that the war would drag on endlessly. It was a cause of great worry to Hennessy that his partner Harry was in active service. Although Robertson Craig was in the intelligence services and not at the front, his journals reveal a man who was left traumatised and angry by his wartime experiences. Every year on the anniversary of his demobilisation he wrote a long entry on the horrors of war and the evils of the colonial project. He claimed that in the event of another war being declared that he would immediately become an Irish citizen in protest. He must have been frank [in as much as censorship would allow] in the accounts he wrote back to Hennessy in Ireland as many years later he wrote, ‘While cleaning up I found the letters I sent to Tony* during the war. I started to read them – and I wish in some way that I hadn’t.’

Hennessy made a number of works during the war that demonstrate his engagement with military events. One entitled Still Life with Newspaper shows a bunch of flowers resting on a newspaper, but a closer reading of the text on the paper shows the headline ‘Allies Land in Fra…’, a clear indication that he wishes to record this momentous day. It is also a sign to the viewer that narrative clues can be easily accessible in the most apparently mundane details of Hennessy’s works.

Another use of newspapers at this time is to be seen in York Street. Here one woman can be seen reading the newspaper on the landing of a building. Another woman looks out nervously from her doorway. We wonder if some news is expected from the front – or worse, a list of casualties. York Street, off St Stephens Green in Dublin, was the site of a terrace of grand Georgian houses that had become some of the worst tenements in the city. They were pulled down in the 1960s to make way for modern social housing. Many photographers like Elinor Wilshire had recorded them before this as their condition was so shocking. In York Street Hennessy was documenting some of the grimmest poverty to be found anywhere in the country. Large families were crowded into single rooms; there was almost no sanitation, and privacy non-existent – a feature indicated by the nosy-neighbour who is ever-present.

But he is also drawn to the incongruously beautiful architectural setting of that poverty. The oculus with its stained-glass detail is as much the subject of his painting as the two women. This juxtaposition of faded grandeur and contemporary poverty was a subject he would return to in the mid-60s in works such as The Princess and the Tinker Children.

Portraits

Six years later in 1945 Éamon de Valera infamously called to the Ambassador’s house to express the condolences of the Irish people on the death of Hitler. This act caused outrage internationally and he was denounced as a traitor on the front pages of The New York Times and The Washington Post. De Valera had insisted on a policy of strict neutrality throughout the war, closing the borders of the Free State to Jews and other victims of Nazi persecution. According to Alan Shatter, Irish neutrality during the Second World War has been lauded as a high moral principle worthy of support and praise, but the reality was that it had more to do with hostility to the British government and the view of its continued occupation of the “Six Counties” than with morality. De Valera and his government were well aware of Nazi atrocities and the ‘final solution’ by the time Hitler committed suicide so commiserating on his death was a ‘morally repugnant and indefensible act’. President Mary McAleese interviewed in 2005 said that she ‘doubted there was an apology big enough that could be offered’.

The story of the Hempel children was compelling. Liv had moved with her family to Dublin at two years of age and lived there until she was seventeen. Two of her younger siblings were born in Dublin. At first she was educated by a governess, a Russian Baroness who had fled to Germany during the 1917 revolution. Baroness von Offenberg had been working for a Jewish family in Nurenberg in the 30s but had to resign as an Aryan could not work for Jews. Her former employers later disappeared and she was ‘relieved to escape rotten Germany’ as an employee of the Hempels when they departed for Ireland in 1937. The Baroness remembered dancing with de Valera at balls in the official residence. After the war she moved to Achill Island where she married a local man and lived quietly until her death in 2015. Later Liv attended the Loreto Convent, Foxrock where she made some life-long friends. When interviewed in 2011 she said ‘I have always loved Ireland and to this day I still feel Irish, as I did when I left in 1950.’

At the end of the war her family were granted asylum in Ireland but in accordance with Allied policies her father was not granted permission to work. To earn an income for the family her mother set up a bakery called ‘Olga’s Cakes’ and sold the produce locally in Dun Laoghaire. In 1950 her father was offered a job in the diplomatic service in the new Federal Republic and returned to Germany with his wife, Liv and her sister Agnes. Her brothers Andreas and Constantin remained in Ireland but the house was burned down in an arson attack soon after they left. Of course we see nothing of this complex history in the innocent face of the four-year-old child drawn by Hennessy. The portraits he made of Liv’s parents Eduard and Eva were sold in Germany in the mid-1950s and their whereabouts are now unknown. It would be useful to know if Hennessy had afforded us any psychological insight into his adult sitters.

There may have been some ambivalence on the part of the artist to accept the commission as when he did, war had already been declared so he was colluding with the enemy. As a gay man he would have been aware of the Nazi’s persecution of homosexuals in 1930s Germany. But whatever his misgivings, Hennessy was not in the financial position to decline any commissions. Politically we have to assume that Hennessy was pro-British as his father and step-father had both been officers in the British Army. Henry Robertson Craig was in active service and added to this his friend Elizabeth Bowen is well-known to have sent reports on the situation in Ireland to MI5 during the war. In fact Hennessy himself was not above suspicion on this front. According to Kathleen Vandenberghe when Robertson Craig came to live in Ireland with Hennessy in 1946, ‘the local people around Kinsale believed that two British/Scottish artists arriving in their midst so soon after the war must surely be spies.’

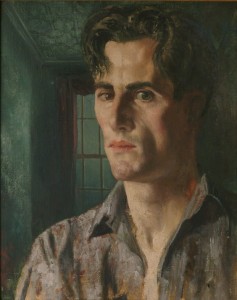

Another portrait completed during the war was of Denis William Hamilton Hurley (1945). This was not a commission, but like the African portraits that would follow in the 70s, Hennessy asked Hurley to sit for him simply because they were friends and Hurley was so handsome. Hurley was a student of medicine at University College Cork and an amateur painter. He took lessons from Hennessy and continued to paint throughout his life. Hurley’s gaze is arresting and magnetic. His face has not been described symmetrically but Hennessy has split his expression. His left eye is wide open, somewhat startled, but also a little hunted. His right eye is harder with his lip curling to an almost-sneer. The manner of depicting the eyes can be compared to Hennessy’s Self-Portrait of the same year which has a similar expression but Hennessy casts his own face in a deep shadow while Hurley’s face is sharply highlighted.

Portrait of Denis William Hamilton Hurley, 1945

courtesy of The Irish American Cultural Institute’s O’Malley Irish Art Collection

The portrait of Hurley seems almost like an act of narcissistic reflection on the part of the artist. The two men are very alike, but Hurley is a little more perfect in every way. From the refinement of his nose, the masculine square set of his jaw and the sensuous V of his jugular notch, he is both warmly beautiful and austerely unavailable. It is without question one of the most successful of Hennessy’s early portraits and one of the few portraits of men (aside from self-portraits) that survive from the 1940s.The majority of Hennessy’s portraits from the 40s and 50s are of girls and women. They are private family commissions gained through personal connections. Portraits of men at the time often had an official function, commemorating the president of an association or board. In 1945 Hennessy was still a young and relatively unknown painter; official commissions went to better established painters like Seán O’Sullivan. After Hennessy had gained a level of financial security in the 60s he almost entirely stopped accepting portrait commissions.

Portrait of a Woman (c. 1945) is a good example of a private commission of the period. Although she is exquisitely painted, Hennessy’s engagement with her entirely lacks the pleasure and sensuality that he derived from painting William Hurley. Compare their hair styles: Hurley’s is carelessly tousled as if his fingers have just run through it, while this woman’s hair is set and lacquered – not to be touched. Her blouse has a high neckline and there is no suggestion of a warm body under her clothes which contrasts to the low-buttoned shirt worn by Hurley that hints at a state of undress. She has a still and frozen aspect, Hennessy seems unable to breathe life into her as he had been with the portrait of Hurley.

It is possible that he was aware of this shortcoming in the work for, as if to compensate, he places her within a demonstration of virtuoso painting. She is standing by a window through which we see Dublin and the dome of the Four Courts far into the distance. Above her head, the curtain rail cuts into the middle-ground creating another layer of space and perspective. The curtain-rail has a trompe l’œil effect creating a startling three dimensionality, a classic display of bravura that Hennessy would greatly develop in his later work. The curtain hanging from the rail is the same brocade that forms the backdrop to Hennessy’s Self-Portrait of 1945 which assists in dating the Portrait of a Woman. But as of yet, research has not identified the sitter.

A slightly later portrait Mrs Cedric Cruess Callaghan was exhibited at the RHA in 1947. Geraldine Cruess Callaghan was married to a prominent Dublin businessman and in this commissioned portrait there appears much more warmth and collusion between artist and sitter. Geraldine (née) Mitchel was a famous beauty and in 1938 won the ‘Dawn Beauty’ competition. She had entered the pageant as she wished to raise her profile, become better known as an actress, and move to Hollywood. This was a good course of action to take; the previous winner of the competition had been none other than Maureen O’Hara who went on to have a great career as an actress. But Geraldine’s plans were scuppered by the outbreak of the war and the impossibility of international travel. She got a part in a movie being shot in Belfast, but other opportunities were few in a country with such a small film industry. Geraldine quit acting and married Cedric in the early 40s. This portrait was commissioned five or six years after their marriage, but she commemorates that day by wearing her elegant lace wedding blouse for her portrait.Compared to the earlier Portrait of a Woman, the focus of this work is definitely the model – not the painter’s skill.

Geraldine sits on the striped pink and white sofa in Hennessy’s own drawing room. Her pose is relaxed, a half-smile begins to form on her lips and there is a mischievous twinkle in her eye. The background of pattered wallpaper has been loosely sketched in. Hennessy doesn’t need to resort to visual trickery to create a marvellous image. Cruess Callaghan seems to look out at the painter with affection, as if there was laughter in between pauses in painting. She and Hennessy shared a fondness for gossip and fun. Many years later she was famously present on the night that C.J. Haughey met his future mistress Terry Keane.

On the other side, the daughter of Hennessy’s great friend Dr William Fegan remembers her father’s appetite for gossip, and when Hennessy would visit that ‘wicked laughter’ could be heard from the next room. Hennessy’s portrait of Cruess Callaghan communicates some of this complexity. She is no empty-headed beauty. She is very present in the artist’s studio; lively, alert, bright. There is a relaxed informality about her, but her eyes have a steely glint that suggests she is not to be trifled with. The portraits of Cruess Callaghan and Hurley have far more in common than the Portrait of a Woman. Cruess Callaghan shows none of the frigid stasis of the earlier picture. Her neckline is high, but feminine and not severe. The form of her left arm can be seen through the gauzy fabric of her blouse. As with the portrait of Hurley, the artist reveals a little touch of unrequited love, and it is this bond between artist and model that makes for such great portraits.

The hint of attraction that elevates those portraits is found twenty years later in the portraits Hennessy makes of young African men. The names of the men recur, suggesting on-going friendships or relationships. Kassim, Ali, M’hamed, all appear more than once in Hennessy’s pictures. They are uniformly young and handsome, a contemporary Doryphoros of sorts, celebrations of male perfection. The portrait of Ali the Thief (1978) is seductive. One thoughtful viewer observed that the title could be an abbreviation of Ali the Thief … of my heart; a romantic reflection on the interaction between artist and model. Unfortunately, unlike Hennessy’s Irish models whose identities are generally known; we know almost nothing about the African sitters.

back to top>

German Sublime tradition

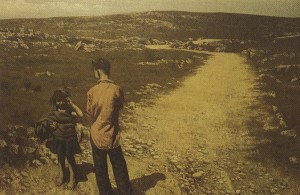

In works like Lake Island (c.1965), and Boy with Pony, Killarney (1968), Hennessy takes the German sublime tradition of the Rüchenfigur [a figure seen from behind] and places it within the tradition of the representation of the west of Ireland typified by Paul Henry. The Rüchenfigur is most familiar from Caspar David Friedrich’s iconic Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). Friedrich (1774–1840) was the prime exponent of the German Romantic Style. His paintings are still and mysterious – qualities that surely endeared him to Hennessy. The foundations of Romanticism were laid by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) and Immanuel Kant (1724-1804).

Essentially a reaction against the pure rationalism of the Enlightenment, they created a philosophy that integrated emotion and sensuality with an awareness of God and his creation. Rousseau argued that ethics emerged from the emotions – not reason or morals. His famous quote ‘Man is born free, but is everywhere in chains’, expresses the idea that man is inherently good and compassionate, but corrupted by society. In Lake Island, Hennessy’s use of the Romantic convention points in two directions. All men are good, all are created in God’s image, and the private beliefs of a citizen do not preclude them from participation in society. On the other hand, the image of the landscape in which Hennessy’s figures are found, was one co-opted by a State that abhorred their nature. Rural Ireland and the west become synonymous with backwardness and intolerance. A Valley of Squinting Windows with all of the squalor and hopelessness found there. Coming from the artist who made De Profundis one can read these images as men grappling with the problems of their sexual identity and the anxiety and loneliness they are experiencing. The use of the Rüchenfigur as a device has the function of activating the viewer; we see the world through the protagonist’s perspective and we empathise with his experience.

In order to build a narrative around Hennessy’s figures it is useful to examine a group of works in this theme. Beginning with In the Studio (1944), we see the artist moving beyond allusion into the intimate spaces of lived experience. The title suggests we are looking at a model, but if that were the complete picture, then Hennessy could have presented a straightforward life-study of him rather than this somewhat stolen reflection; the glimpse of a private moment.

Young men continue to be seen in isolation in works like Adieu (1975) which shows a man looking out to sea where a ship is sailing into the distance; we can project that it is taking his lover away. There is a tragic finality to the title, reminiscent of Madama Butterfly, ‘adieu’ is not ‘au revoir’, there is no suggestion that these people will meet again; love may have been found, but it is now lost.

The much-loved Boy and Seagull (1954) from the IMMA Gordon Lambert Collection, shows a young man transferred to an urban setting – Dublin’s Great South Wall. As with Adieu, ships leaving Dublin Port pass by the South Wall on their way to Holyhead, Cherbourg and further away. Could this young man wonder what life might hold beyond the shore on which he stands? Might life hold the possibility for self-expression in a less repressive climate? Founder of the Irish Queer Archive, Tonie Walsh, speaks of emigration thus: ‘If there was a ‘low point’ during the 40s-60s, I would describe it as the haemorrhaging of successive generations of gay men and women to more socially accepting environments abroad. We’ve yet to imagine and calculate the appalling human misery and the economic and cultural loss to Ireland this entailed.’

Boy with Pony, Killarney, like Lake Island combines a solitary figure with familiar depictions of the Irish landscape. This boy is different however; his stripy T-shirt identifies him as of his time – a child of the 60s, that decade of loosening social structures and mores. In his essay for Rosc 1971, The Irish Imagination, Brian O’Doherty argued that the self-imposed isolationism of the period from the beginning of the Second World War until the end of the 1950s was important in allowing Irish art to develop a specific character, removed from outside influences. Yet the consequent insistence on a kind of poetic ‘atmosphere’ as the dominant tendency in Irish art of the 1960s ‘could be considered a last examination and confrontation of a certain minority or subject mentality that never responds to anything directly’. Fionna Barber argues that it is more than this.

‘Rather than just being a hangover from the miasmic 1950s, there is a sense of deeper emotional, cultural and political roots for notions of the intuitive invoked by many Irish artists during the following decade. Landscape continued to dominate, yet its meanings had undergone a series of transformations since the early part of the century.’

The statements of both O’Doherty and Barber are well illustrated by Hennessy’s treatment of the landscape. His works are both possessed of a poetic atmosphere, but they also participate in rewriting the meaning of the Irish landscape. By conflating the beauty of the sublime with states of emotional distress he opens up a space for the other, whoever that might be. In many ways he was ahead of his time.

Before the contemporary language around ‘coming out of the closet’ was in general use, Hennessy was perceptive and sensitive to the nuances of self-awareness and his characters are shown undergoing a gradual development. He depicts men at different ages in their lives from adolescence to maturity; they are also shown at different stages of their personal development from fear through to acceptance. This evolution can also be seen in Hennessy’s own self-portraits. In the early 1940s he has an anxious and somewhat hunted expression. By the 1970s this has changed utterly and in a work like Cliffs of Étretat (1972) we see a suave, confident character in sunglasses, finely dressed and standing by the sea in a foreign country.

Although the theme of ‘coming out’ or adolescent sexuality has few counterparts in visual art, the writings of two gay Irish novelists offer a literary comparison. Forrest Reid (1875 – 1947) was lauded by Elizabeth Bowen for the ‘unemphatic beauty’ of his writing and E.M Forster described Following Darkness (1912) as ‘A Masterpiece’. In Following Darkness he described the sexual awakening of the teenage Peter Waring. Critics found the unflinching honesty of the book hard to stomach, one denouncing Peter as ‘a subject for the pathologist rather than the novelist’, ‘an evil character who unutterably disgusts’. A later novel, Paul Smith’s Summer sang in me (1972) similarly depicted the undercurrent of sexuality that permeates teenage lives. Set in Dublin’s tenements, Smith focused on the lives of young people in the inner city. Seán Alone is like an illustration of a scene from Smith’s novel showing boys diving into the canal; but it is also a comment of social class, ‘Nice boys’ don’t swim in the canal, their parents take them to the seaside for the holidays.

back to top>

Social Issues – Travellers

The trope of the male figure seen from behind is one that Hennessy utilised to convey multiple psychological states of mind. However there are a number of occasions that [aside from portraiture] when his protagonist turns to confront the viewer. In these works Hennessy moves away from internalised dialogue but utilises the motif to challenge the viewer and address issues of poverty and social exclusion. If the Rüchenfigur is emblematic of a psychological state, then the figure turned towards the viewer is communicating their social circumstances. From the 1940s a number of artists like Gerard Dillon, Nano Reid, Jack Yeats and Louis le Brocquy dealt with the subject of the Irish travelling community.

Some notable examples are Yeats’s Tinker’s Encampment: Blood of Abel (1940) and le Brocquy’s Travelling Woman with Newspaper or The Last Tinker (1947-8). The geographic isolation created by The Emergency meant that many artists like le Brocquy, who returned to Ireland during the war, studied what was around them more closely and looked at the liminal spaces in Irish society. Le Brocquy’s Tinker series has been linked to European Existentialism. Travelling people became synonymous with the refugees all around post-war Europe. Le Brocquy removes the Irish travellers from their specific context and uses them as metaphor for a universal wartime experience. Medb Ruane has argued that these images demonstrate le Brocquy’s desire to offer ‘alternative visions to the narrow template of preferred Irish-ness’ instead asking ‘what being Irish might mean … or what it might exclude’.

Whether as a motif of displaced peoples or an interrogation of national identity, it is clear that le Brocquy utilises travellers as a device; he is not describing an individual or their unique experience. Hennessy’s use of these figures is different. His close friend Sheila Pim was an advocate for Travellers’ rights and he was acutely aware of the discrimination they faced on a routine basis. An early example Children of the Road (1961) shows two girls wearing headscarves walking barefoot along a country road. It is a quiet and somewhat poetic image that might fit into the nineteenth century tradition of genre painting; a simple record of provincial life. The girls’ dress is so poor with their lack of shoes and old-fashioned head-scarves that in 1961 it was surely anachronistic, a romantic memory of an earlier time. The artist’s touch is so light that it would be easy for the viewer to pass over the work without a second thought. Nonetheless, Hennessy’s title informs us that these girls form part of one of the most marginalised and deprived groups in Irish society, Irish Travellers, and so it begs further enquiry. As Hennessy develops the theme of the Irish traveller his images become more complex. The second image shows two children barefoot on the roadside. The little girl is swathed in a blanket and turns to look at the viewer as she rubs her tear-stained eyes. Her brother walks away.

Also entitled Children of the Road it was exhibited in 1964 but it has none of the sentimentality of the earlier version. Clearly these are observed people and the images of them had particular meaning for Hennessy. By this time many photographers like Elinor Wilshire had already made influential bodies of work of the travelling community, but these may have been children that Hennessy himself met and photographed, or who were known to Sheila Pim.

In 1965 the same children reappear in The Princess and the Tinker Children, which is an almost grotesque juxtaposition of wealth and poverty. The central figure is Princess de Broglie painted by Ingres in 1851. Attired in the finest silk gown and fashionable jewels she is the very embodiment of a mid-nineteenth century aristocrat. Despite this, she is listless displaying Baudelairean ennui. Her folded-arm pose is mirrored by the boy to her left, but it is the girl to her right that makes the most startling contrast. She is barefoot with dirty legs, her hair is matted and she clutches a blanket around her protectively. The newspaper clipping pinned to the board states ‘Devaluing rumours foolish’.

In 1965 Britain was in the middle of a currency crisis and on 9 August 1965 the front page of The Daily Mirror helpfully told readers, ‘In brief we’re talking about YOUR job, YOUR stomach, YOUR children’s future.’ Clearly the crisis had the potential to gravely affect the economic well-being of ordinary people. Hennessy’s strange conflating of contemporary traveller children with a Victorian princess might suggest that power and inequality are a result of an inherited economic and legal system. More particularly he may be referring to the history of the Irish travellers as some historians suggest they were displaced during the Great Famine of the 1840s when Princess de Broglie was painted.

The poverty of post-war Ireland appalled many of Hennessy’s contemporaries. While on his way to visit Elizabeth Bowen, Lucian Freud’s patron, Peter Watson travelled to Limerick in 1947. He was charmed by the Georgian architecture and shocked by the abject state of some of the people he met. In the post office they were approached by ‘three little girls with bare feet, matted hair and sores on their legs, begging for pennies’. He gave them some coins and they ‘trailed after him for streets.’

The boy from The Princess and the Tinker Children reappears as Boy with horses on the Seashore (c. 1965), where Hennessy’s trope of the Rückenfigur is abandoned. The traveller boy now turns to challenge the viewer. His gaze implicates us in the knowledge of his social exclusion. He looks wild like the Connemara pony standing beside him but he is no constructed trope of Irish masculinity.

As a compliment to the heroic Irishman imagined by Seán Keating he is a damning indictment of Irish society. Among the travellers, Hennessy finds another type of Irishman. Like the fishermen of Keating’s imagination, they are untouched by British influence, true ‘Celts’; but also a social group that has been marginalised and left behind by the constructs of a new State. Hennessy confronts us with the brutal realities of our state, a Catholic republic in which its citizens are far from the ideals of Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité. It is a state in which some are ‘more equal than others’, but it is certain that travellers and homosexuals are distinctly less equal.

back to top>

Gender, Society, Religion

Returning to Ireland in 1939, he found a country with a different type of sectarianism than that in Scotland. The Anglican Anglo-Irish, as described by his friend Elizabeth Bowen’s novel The Last September (1929), held onto nineteenth-century prejudices and resisted the move towards a more egalitarian society; unlike their English counterparts who had been shaken by the experiences of the Great War through the huge loss of life, and the social mobility that began to be felt there. The counterpoint to this was the unusual amount of influence held by the Catholic Church and Archbishop McQuaid, whose interference in political matters coloured legislation for decades.

Hennessy addressed the complications of Irish religion in highly personal ways interweaving the pagan, classical and Catholic. He examines the peculiar nature of Irish Catholicism, highlighting the thin veneer that sometimes separates it from ancient practice. He also complicates the gender norms within the religion as practiced in Ireland, showing its goddess-centred nature.In 1953 he exhibited The Angel of the Annunciation at the RHA.

The painted stone or wood figures have been removed from their usual context of religious buildings and placed on the shore with the sea glistening brightly behind. Gabriel is the messenger of God, his Classical ancestor being Hermes or Mercury. In the Annunciation, the Archangel Gabriel came to the Virgin Mary to tell her of God’s will that she should carry the Christ child. Mary reacted in four ways from shock through to acceptance that are recognisable in Renaissance painting. But neither the Virgin Mary nor any of the symbolism of the Annunciation is present in this work. Instead of the Virgin there is another figure of indeterminate gender who could be a saint or monk, or it could be the figure of Christ. In the Book of Revelation chapter 10, Christ and the Archangel Gabriel meet on the shore. Gabriel will be ‘robed in cloud’ while Christ will plant ‘his right foot on the sea and his left foot on the land’. It is the part of the Bible that deals with the apocalypse and the end of days.

This is a very difficult painting to interpret. Perhaps Hennessy is suggesting that Gabriel was witness to the beginning and the end – of the conception of Christ and his arrival at the end of the world. Or perhaps it is none of these things and the work should not be read using theological means. These statues on a beach could be just that – signifiers for simpler ideas, removed from their traditional context and now appearing forlorn and ridiculous. With their faded paint they seem like relics from some past age, irrelevant in a modern world. By placing them within the glory of nature, Hennessy points to the real and present power in our lives from whence real joy and inspiration can be derived. Connections to works like Lake Island can be made, where we see a young man look to nature for answers. It is nature, that can communicate – that will be the messenger of the gods; not Hermes or Mercury or Gabriel.These works were read at face-value by some of the Establishment, and in the mid-50s the then Minister of Post and Telegraphs, Erskine Childers, commissioned Hennessy, ‘to paint a religious image in a landscape.’ The resulting picture St Christopher in Landscape (c. 1955) entered the State collection and is now held by the Office of Public Works. St Christopher is the patron saint of travellers and bachelors!

He is represented as a giant carrying the Christ child on his shoulder across a dangerous river. He was a Christian martyr, but never officially canonised, so is not fully recognised by the Church. Hennessy fulfils the terms of the commission by creating a ‘religious’ image, but he sidesteps the content by using a source that exists in popular faith and folklore rather than doctrine.

This privileging of folklore over doctrine is also seen in Pietà (1967), a highly-symbolic work in Hennessy’s oeuvre. A pietà typically shows the Virgin Mary cradling the body of her son, the dead Christ, the most iconic being Michelangelo’s sculpture in St. Peters, Rome. Michelangelo brings pathos and drama to his embodiment of this tragic biblical event. The viewer empathises with a mother’s grief as her son’s body lies limply in her arms. Hennessy inverts these tropes in his painting in which Christ holds a miniature Virgin Mary. The figures are devoid of Michelangelo’s physical naturalism but resemble Gothic sculpture of the fourteenth-century. These works lack the power of high-Renaissance sculpture, but they also represent European religion before the Reformation and the terrible religious wars that followed in its aftermath. The high-Renaissance and the Catholic counter-reformation were contemporaneous. Hennessy’s Gothic figures represent a simpler time in history before religious schism created seemingly endless conflict.

The landscape in which Hennessy places his Pietà is the plain at the bottom of Ireland’s holy mountain Croagh Patrick in County Mayo. Croagh Patrick has been a site of pilgrimage for more than five-thousand years and the tradition is unbroken as tens of thousands of people continue to climb the mountain every year. It was a site of ancient burial and sacrifice marking the changing seasons and harvest times.

The landscape around the mountain is littered with megalithic sites that prove its function as a calendar. St. Patrick is reputed to have fasted for forty days and nights on the summit of the mountain as part of his Christianising of Irish pagan sites. Hennessy makes the pagan reading of this image explicit through his alignment of the moon with the mountain – a clear reference to the pagan calendar as well as to the goddess for whom the moon is a symbol.The cult of the Virgin Mary is particularly strong in Ireland, as it is in Latin America. It is thought to be a remnant of Goddess worship in pagan times that also survives in Sile-na-Gig carvings on churches and other public buildings right up to the medieval period. What is telling about Hennessy’s image is the manner in which he diminishes the size and importance of the mother in this work. She is infantilised, her hands supplicating in prayer and in the complete control of her son. It is as if the Goddess has been supplanted by Christ.

Roman modes of thinking arrived in Ireland along with Christianity and women’s rights would be eroded in the coming centuries. Ireland in the 1940s and 50s was a bleak place for women. Unmarried mothers were incarcerated in Magdalen laundries and their children placed in industrial schools where often they were subject to systematic abuse. According to Edain McCoy ‘in comparison with her contemporaries in Greece and Rome, a woman in Celtic Ireland held an enviable position … Irish women were permitted to own property, to seek divorce and to retain their own property and expect the return of their property afterwards. They could demand an honour price for the murder of one of their kinspeople … and they could take grievances before the judge. The child of an unmarried woman was not declared illegitimate; no such stigma existed among the Celts. All freeborn people had a rank that automatically entitled them to certain rights under the law.’

Women’s position within the Christian church is also referenced in St. Joan (c. 1944). A small portrait of Joan of Arc made during the war, it was painted around the same time as Cathedrals and De Profundis. Joan of Arc was the French teenager who in the early fourteenth-century had divine visions and said that God had instructed her to take control of the French army and lead them to victory. During the Hundred Years’ War, the French had suffered successive defeats against the English for a generation. Joan’s arrival heralded a turning point for the French and her advice to the generals was heeded as being divinely inspired. But soon after, Joan was captured by the opposing English forces and put on trial for heresy and witchcraft. Added to the religious charge, she was also accused of cross-dressing in men’s armour and wearing her hair short like a man.

She was burned at the stake in 1431, only two years after the siege of Orleans. Joan was a woman who meddled in the affairs of men and was punished for it. The English hoped to have her indicted for witchcraft as this would discredit the French king, Charles VII, a man not only under the influence of a woman, but also a woman who was a witch! Joan attempted to transcend her gender and move beyond its prescribed limits and this was enough to have her accused of a capital crime. The cross-dressing charge was picked up on by later writers like Vita Sackville-West who suggested that Joan was a lesbian in the biography she wrote about her in 1936.

John the Baptist, subject of Landscape with John the Baptist and Monk (1955) is another biblical figure depicted by Hennessy. St John was the prophet who preceded Christ and is thought to have baptised him. John spent his life preaching the word of God until he was imprisoned by King Herod after he admonished him for divorcing Queen Phasaelis and marrying the wife of his brother; a story with echoes of King Henry VIII, Arthur and Katharine of Aragon. What happened next is well recorded in cultural history. Herod’s new stepdaughter Salome danced. He lasciviously promised her any gift she wanted. She chose the Head of the Baptist, and a new martyr was created.

A thread runs though many of the religious subjects that Hennessy approaches; that of good people being betrayed by the system. He shows us that doing the ‘right’ thing or speaking the truth is never wise when faced by the power and money of institutions and it seems that this was a personal issue that he felt deeply. As a gay man, the judgement of the church weighed on his mind but he seems to have worked out his own feelings on the issue quite clearly. In 1898 Roger Casement expressed the feeling that his sexual orientation was made by God and not a choice, ‘I only know ‘tis death to give My love; yet loveless can I live? I only know I cannot die And leave this love God made, not I.’

Hennessy and Craig clearly thought about, and discussed the issue of their homosexuality and religion. In 1951 Robertson Craig noted, ‘Someday (I don’t think) they will teach children at school to understand their natures and to act accordingly – it would be much more useful than geometry. What would our hypocritical, base and wounded civilisation make of that? Our black hateful priests and ministers? It would put some of them out of business. For them and the wreckage they have scattered around them – my contempt.’ Piety, conservative religion and those that followed it were a focus for this ‘contempt’. In the letter Hennessy wrote to Alex Allan in 1946, he described scenes of ‘pious clap-trap’ as ‘nauseating’. Robertson Craig’s journal also recounts more than one occasion when he and Hennessy spent some hours arguing with the artist Patrick Pye and his mother on matters of spiritualty. On one occasion he notes, ‘when we left I think we had at least made him think a little.’

Hennessy’s broken statues were of a type to be found in many a Catholic home in rural Ireland in the 50s. The statues speak of simple belief, but also of the hypocrisy and, sometimes, cruelty of that period. Hennessy shows us an institution that is (or always was) out-of-touch, disconnected from reality, a relic of history. He also alludes to different times when people were more equal and less controlled by state institutions. To a contemporary eye these statues might seem kitsch and it appears that Hennessy was interested in pushing at the boundaries of ‘good taste’. In the Studio shows a Staffordshire figure sitting on the chimney piece. This and other broken pieces of figurative ceramic were used repeatedly by Hennessy in different configurations. They are almost certainly tongue-in-cheek in tone. Hennessy enjoyed visual puns – his home on Raglan Lane was filled with plays on morality and propriety. For example in the bathroom, pictures of Victorian lords and ladies were pasted to the wall. Their torsos were left as found, but he had jokingly painted out their trousers and skirts making them appear naked below the waist.

This layering of potential readings is also found in The Spanish Christ (1961) and Crucifixion. Inspired by visits to the Semana Santa in Spain in which the Passion of Christ is re-enacted, Hennessy created these works in response. Hennessy was impressed by the spectacle and pomp of the participants, but doubtful of the sincerity of such outward acts of piety.

It is clear from the Crucifixion that he is referring to a re-enactment, as the figure’s hands and feet are bound rather than nailed to the cross; he also departs from the convention of a long-haired and bearded Christ. This man seems young and attractive, with soft hair and a lithe body. Hennessy’s depiction of Christ with an attractive body is gently subversive. A pious viewer would have considered it an immoral act for a homosexual to think about Christ ‘that way’. This interplay of religious iconography and the homoerotic anticipate the practice of artists like Derek Jarman by several decades.

In 1971 the noted scholar on Vermeer, Christopher Wright, came to Ireland looking at historic paintings. He was very struck by this Crucifixion by Hennessy and catalogued it along with 17th and 18th century paintings. This was fortunate as Crucifixion was later destroyed in a house fire in which tens of Hennessy pictures were lost. Wright’s black and white illustration is all that survives.

back to top>

Prostitution

Any discussion of Hennessy’s work must acknowledge the importance of Henry Robertson Craig in his life. They shared adjoining studios from 1947 through to Hennessy’s death in 1980; they critiqued each other’s work, discussed the work of other artists, music, and the shared intimacies of their lives. The Mandarin Robe, which until recently was attributed to Hennessy was painted by Robertson-Craig in 1951. It is a portrait of a beautiful young man called Fitzgerald who owned the kimono.

Robertson-Craig was drawn both to the man and his costume and asked him to sit for him. Fitzgerald agreed and the portrait took around a week to complete. Shortly after, it was exhibited at the Dublin Painters Gallery in a solo exhibition of Robertson-Craig’s work. It is typical of the orientalism of the late nineteenth century and stands up to comparison with Hendrik Breitner’s series of works loosely titled Girl in a Kimono. The gorgeous oriental fabrics and chinoiserie background evoke the decadence and aestheticism of Edith Wharton, Henry James, or most particularly Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). But there are other similarities to Wilde’s novel as the Neo- Platonic linking of beauty and goodness were sundered apart.

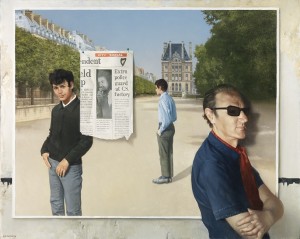

Male prostitutes are the subject of Hennessy’s Self-Portrait with Figures (1972). They are represented as young men standing in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris, a well-known cruising area since the nineteenth century. In the 1960s it became notorious; the following report was carried by a French tabloid newspaper calling on the police to end ‘the scandal of the Tuileries’. ‘What goes on there every day, in the heart of Paris, in a place where children come to play, is revolting. The Tuileries Garden has become the number one meeting place for homosexuals in the capital … They come and go with their effeminate walk. One hears … their indecent giggling. There are dozens of them. They seek each other out. They wink, accost each other, arrange rendez-vous … It’s appalling.’

In Hennessy’s work a large image of the Tuileries is pinned to the studio wall and the artist stands in front of it. Two young men are seen with their hands in their pockets waiting aimlessly… loitering. The figure on the left is young and handsome. His hands frame his groin and he looks at the viewer questioningly and with an inviting half-smile. The figure on the right seems poorly dressed, his shoes are worn and his trousers ill-fitting, suggesting a level of economic hardship. As if by contrast, Hennessy shows himself nattily dressed with a finely-detailed shirt and red silk cravat. He wears his trademark dark glasses and his hair is swept back from his face. His back is to the scene. Perhaps he is telling us that this part of his gay life is in the past; or the inclusion of the newspaper clipping might indicate a topical issue that needs to be discussed.

As with the earlier Boy with Horses on the Seashore the gaze of the young man is a challenge to the viewer. There is a demand to acknowledge him, to see him. On a superficial level the viewer can recognise his attractiveness but, as with other works by Hennessy, at one remove the realities of his daily existence point to social inequality and injustice.

It was certainly Hennessy’s intention to offer a queer reading of this painting as the red necktie he is wearing was code for ‘homosexual’ since the 1920s. The red tie as signifier was present in one of the most notorious works of queer art, Paul Cadmus’s The Fleet’s In (1934) a work that caused a scandal when it was exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery, Washington D.C.

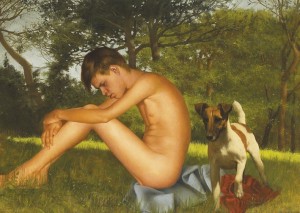

In his late work, Hennessy displays an awareness of queer visual art and a desire to contribute to that discourse. He did this in his typical fashion of fusing contemporary social concerns with the modes of the old masters. His Boy with Dog (1979) is a direct quotation from Hippolyte Flandrin’s (1809-64) most iconic work Jeune Homme Nu Assis au Bord de la Mer (1839, Musée du Louvre).

Sites of sexuality

Hennessy’s painting In the Hammam was made before 1968 but never publicly exhibited in his lifetime. It formed part of a series of at least four life-size canvasses depicting male nudes and painted in his Raglan Lane studio. The house at Raglan Lane was used by Hennessy and Robertson Craig during the summers when they returned to Ireland. In wintertime, the house was used by the daughters of Hennessy’s great friend and patron Dr William Fegan.

In 1970 Hennessy sold the house and most of the studio contents to Dr Fegan as he and Robertson Craig had decided to make a permanent move to Tangier. Dr Fegan’s daughter, Jenny Richardson remembers her mother sorting through the studio contents Hennessy had left behind. A number of large canvasses were screwed together face-to-face. She took them apart and was surprised to be confronted with these bodies. Not knowing what to do with them, she sent them and quite a few other works into storage at their house in County Kildare. Sadly, a number of years later the house burned down and with it Hennessy’s nudes – bar one.

Another member of the family, Sally Fegan-Wyles, remembers finding a small journal [location now unknown] that had been mislaid by Hennessy and left behind in the studio. She read a section of it and found it disconcerting. It recounted a sexual encounter between him and another man in a hammam. While now she is unable to articulate why, she felt that it had been a negative experience, that this other man was some kind of malign force. Fegan-Wyles’s recollection suggests that there is an auto-biographical narrative to In the Hammam, that it is a depiction of a lived rather than imagined experience.

In the Hammam still has the power to disconcert the contemporary viewer. When it was exhibited after Hennessy’s death at the Important Irish Art sale at the RDS in 2001 it was hung in a back room as it was considered too risqué to be seen by the general public. When one considers what is broadcast on television or the cinema today, fully nude images of men are still exceptional. Looking back in time, the Renaissance convention was to show small genitals. A man’s sexual organ was a source of embarrassment so it was shrunken or hidden. One only needs to think of Michelangelo’s David (1501-1501) to appreciate the aesthetic choices made by the artist. This is possibly why Hennessy’s picture is so arresting, the large and frankly depicted penis of the main figure is still unlike anything we are confronted with in wider culture.

The Hammam or Turkish Baths were identified as sites of erotic interest by artists like J.A.D. Ingres in the mid nineteenth century. His Turkish Bath (1862, Musée du Louvre) shows naked women sitting dreamily around a pool in highly ornate surroundings. Women of different races are depicted who bathe, dance, play music, and fondle one another. The descriptions of oriental harems, where powerful men had possession of innumerable women, held a fascination for western men.

In 1862 a Sultan still sat on the throne of the Ottoman Empire, breathing an air of possibility into these erotic scenarios. The carpets, arabesques, deep colours and decoration of the Orient became conflated with notions of easy sexuality in the western imagination. In Victorian England, concerns of personal hygiene led to the opening of many public bathhouses and by 1916 in London there were twenty-five Turkish Baths in operation. The combination of naked men and the erotic connotations of the orient led to a number of them becoming a focus for homosexual rendezvous.

By the 1930s this was so commonly known among gay men that it became an object of humour. When visiting Lord Berners at his house in Faringdon, Cecil Beaton signed the guest book with his business address as ‘Hamam Baths’ and his profession as ‘Masseur’. The ubiquity of Turkish Baths as sites of sexual activity suggests that In the Hammam is not necessarily situated in Tangier, it could as easily be London, Paris, or any other major city that was a focus for gay men.

In the Hammam is more than the study of sexual interplay, it can be compared to Self Portrait with Figures, Atlas Beach or Robertson Craig’s Last Customers at the Philbeach (c.1982); all of which deal specifically with the locus of gay men’s lives. The Philbeach was a well-known gay bar in a hotel in Earls Court in London that closed only recently. Atlas Beach shows the model Kassim on the roof of ‘Edward’s Bar’ in Tangier, another location frequented by gay men. And as previously pointed out, the Tuileries in Paris had been a focus for gay men for two centuries. Aside from some exceptions already noted, Hennessy and Robertson Craig’s honest depiction of the different facets of their gay lives separates their practice from their contemporaries. Although their academic style of painting was conservative, it was radical to adopt as subject-matter the sexual or homo-social lives of gay men.

Images like In the Hammam or Cliffs of Étretat are neither erotic nor pornographic. They do not describe a sexual act and while they may be titillating, they do not elicit a physical response. They have more to do with the geography of sexuality than sex – a concern shared with the work of Paul Cadmus. Putting In the Hammam aside, the nude males that were publically exhibited by Hennessy including Boy with Seagull, Cliffs of Étretat, In the Studio and The Yellow Ribbon all share a common trait: the model has a slight physical frame.

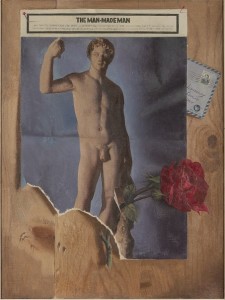

The Classical Greek ideal of physical perfection seen in the Doryporus (Horseman pass by) or the Kouros (Man-made Man and Rose) was adopted by fascist regimes in the 1930s and 40s as a prototype for Aryan perfection. German National Socialism strictly defined what was acceptable as an ideal Aryan body and proscribed all other visualisations. The Degenerate Art exhibitions juxtaposed ‘Good, Healthy, Moral’ bodies by artists such as Arno Breker, against those by artists like Otto Dix that showed ‘immoral’ scenes populated by ‘corrupted’ bodies.

Hennessy presents us the Classical ideal – but only ever at a distance – through a direct quotation of the art of the past as seen in Horseman pass by. His visualisations of reality show just that, real men with undernourished bodies and knobbly knees. They are vulnerable rather than heroic or hyper-masculine. This serves to distance Hennessy’s bodies from Fascism on one side, but also from the fantasy homo-eroticism of John Koch on the other. The physical vulnerability of the model for In the Studio or Boy with Seagull adds an emotional narrative to the scene and can elicit diverse responses from empathy to protectiveness.