Influences and Affinities

Although Hennessy has few peers in terms of his subject matter, other artists working in the same period make an interesting point of comparison to see how they handled some similar themes.

The American artist John Koch (1909 – 1978) was a near contemporary of Hennessy’s. He lived through the Great Depression, the Second World War, and was witness to the rise of Abstract Expressionism as it swept through New York in the post-war years. He and a number of other artists founded an art review called The Realist as a counterpoint to the non-objective art that was dominating the market.

Based in New York he had an independent income and did not need to make a living from painting. He was dismissed as a ‘society painter’ and Hilton Kramer described him as ‘reactionary’ that ‘he prided himself on being at odds with the art fashions of his time’; something that sounds quite familiar when one considers Hennessy’s opinions on non-objective art and the reception he received from some critics in Ireland.

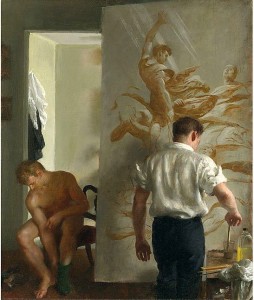

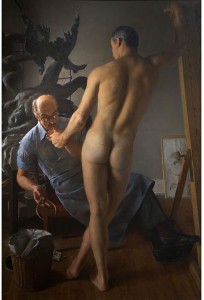

Unlike Hennessy, Koch was gay but married and in the closet. He painted high-society New York, cocktail parties, interiors and still-lifes but these don’t appear to interest him as much as when he depicts naked models. His works showing artist and model that are most revealing and charged. After the sitting shows a handsome blond man pull on a sock as the artist cleans his brush. The poses of artist and model are beautifully mirrored and there is an unspoken tension between them, an awkwardness as the model now feels naked and the artist averts his gaze.

The Sculptor (1964) is the most homoerotic of his works. The position of the artist’s mouth, the oral activity, the flame that connects the two men are all incredibly potent and sexual. The muscular model fills the entire composition with his body, his right arm and leg forming a diagonal line through the whole picture.

The artist who is seated with his legs outstretched forms an intersecting diagonal. Tellingly the line of his body is shorter and lower, the artist is in every way submissive to the model as he lights his cigarette. The picture suggests that the social and economic differences that might create a power imbalance between the artist and model are entirely overtaken by youth, beauty and virility. The success of this work lies in the realisation that both artist and model are aware of this dynamic – it is the model who is in control, who metaphorically lights the cigarette.

Although exceptions exist, in general Hennessy does not show us the interaction between artist and model, it is suggested. But as with Koch’s work, in Ali the Thief or Walled City youth and beauty are celebrated. In the Studio (1944) shows a male figure reflected in a mirror. On the chimneypiece rest a Staffordshire figure and a jam-jar filled with wild flowers. These create an array of textures described in paint, from cold pottery and the softness of petals to the warmth of the skin seen reflected in the glass.

The nude has been a subject for artists for centuries, but female nudes vastly outnumber males who are more normally seen as anatomical life-study. Hennessy breaks with tradition by sexualising the male figure. He gives us an indirect reflection, a furtive glimpse of a private moment between the artist and another man. It moves beyond allusion into the intimate spaces of lived experience and places the viewer in the uncomfortable position of voyeur. It is comparable to Édouard Manet’s (1832-83) seminal work Olympia of 1863. This was one of the first works to implicate the male viewer of the nude by granting agency to the female model who looks directly at the viewer in a direct challenge to his gaze. But Olympia is also posed and ready to be painted, she is ‘nude’. Hennessy’s figure is different; he is naked. To distinguish between the two terms, a body without clothes that might cause embarrassment is naked. This is different to a body posed and idealised by an artist. That is the nude, an uninhibited celebration of the body. One of the flowers in the vase partially obscures his body which has the veiling effect of rendering this man naked. His slight form is not at all like the virile masculinity of a Michelangelo but it is vulnerable in its nakedness. In the nineteenth-century, Manet shocked his viewer by giving a woman agency; Hennessy confronts by stripping a man of his – an equally subversive act in the twentieth.

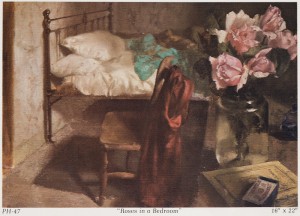

Interaction between people is always at a remove in Hennessy’s work, figures may be seen in reflection or as images pinned to the wall but he avoids depicting exchanges; he leaves it to the viewer to imagine the relationships between individuals or artist and model. Although Hennessy avoids depicting interaction he does allude to it. Roses in a Bedroom appears like a romantic still-life or genre scene but the image of an unmade bed is also a recognised signifier of sexual activity. As with In the Studio, the viewer sees the flowers first, they are fore-grounded as the ‘subject’ of the picture but the background of Hennessy’s pictures is where the ‘subject-matter’ is to be found.