Patrick Hennessy: Life

[Taken from an essay by Kevin A. Rutledge, from Patrick Hennessy: De Profundis. IMMA, Dublin, 2016 Click on the chapter titles below to jump to the relevant section, or scroll down to continue reading.]

Family and Early Years

The Dundee Years

The Hospitalfield Experience

Arrival in Ireland

The Contemporary Painting Scene

Fellow Artists, Ireland and the 1940s

1950s – the Established Painter

The 1960s – Life Changes

Hennessy’s Last Decade

Hennessy’s Demise

Hennessy’s Position in the Firmament of Irish Artists

The Letter “My Dear Alex, “

Alexander Allan and his wife Hilda were contemporaries of Hennessy and Robertson-Craig at Dundee College of Art. The letter is undated but written in the early spring 1946.

Manuscript from a Private Collection.

Copy held in the Patrick Hennessy artist file, IMMA Collection.

Family and Early Years

Patrick Anthony Hennessy was born on the 28th August 1915 at No. 2 Shandon Terrace, Cork. His father was John Hennessy, a Company Sergeant Major in the 2nd Leinster Regiment in the British Army.

John Hennessy was born in 1878 at Convent Street, Listowel, Kerry to Denis Hennessy, a man’s agent, and Honora Hennessy, née Meehan. His mother, Bridget Ring, was born in 1889 at Old Abbey, Fermoy to William Ring, a labourer, and Elizabeth Ring, née Brien. Little is known of Bridget’s family except her father laboured as a gardener at the Abbey, and the Abbey was very probably where Bridget was in service. John Hennessy, who was then stationed at Birr Military Barracks, married Bridget Ring on the 7th January 1905 in the Roman Catholic Church of Fermoy.

John and Bridget went on to have six children, Denis, Mary, Lily, Eileen, John and finally Patrick, all renamed within the family where Patrick was known as Tony. The Hennessy family moved about in the various British Army Barracks, John being born in 1913 in Dundalk two years before Patrick was born in Cork.

In 1917 the fortunes of the Hennessy family changed dramatically. Sgt Major Hennessy was posted to serve on the western front in Flanders and was killed on 21st July 1917 at Passchendaele, Belgium, in one of the great battles of the First World War. His death left his wife Bridget, aged 35, with very little income and the task of raising six children, the youngest Patrick not yet two years old. In order to support the family this determined, forceful woman set herself up in business repairing uniforms for the military and police and providing a cleaning service at 1/6d a uniform. It is entirely possible that during this period she met the man who later became her second husband. John Duncan was a Scot serving in the Royal Irish Constabulary stationed in Cork at that time and by all accounts was a kind faithful man who took on the role of father of six children. He married Bridget Hennessy on 6th May 1921 in the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Cork, his residence at the time of marriage being Shandon Barracks. Bridget’s was 6 North Abbey Square.

The entire family left Ireland when John Duncan resigned from the R.I.C. and moved to 9 Bridge Street, Arbroath, Scotland, where he had relatives and where he commenced employment as a flax mill tenter. Patrick’s brother John recalled aspects of his life in Cork when he was eight years old for his daughter Lily, including the burning of Cork followed by rioting and looting. This was shortly before the British Army left Ireland in 1922.

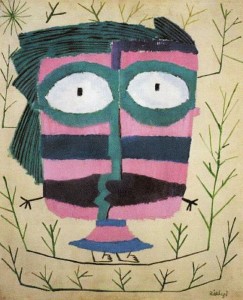

Self Portrait, 1940

watercolour and ink on paper

courtesy of The National Self Portrait Collection of Ireland at the University of Limerick

The Hennessy family settled into their new life in Arbroath with their formidable mother and stepfather. John and Patrick were enrolled in the local primary school in Arbroath where they were the only Catholics in their year. In the academic area, Patrick started to show promise and was enrolled in Arbroath High School. There he came to the notice of Patrick Ingles, principal art teacher at the High School, who encouraged him to develop his artistic skills. In his final year at Arbroath he won the special history prize and the Art Medal. These awards convinced his family that Patrick’s artistic talents should be developed and he was enrolled in the Dundee College of Art at the age of eighteen. Considerable sacrifice was made by the Hennessy siblings to pay for their brother’s further education. Their efforts and contribution were rewarded by his continuous success, winning the annual prize every year for four years and culminating in the award of the Travelling Scholarship in 1938/39.

The Dundee Years

The records show that Patrick Anthony Hennessy, just turned 18, residing at 9 Bridge Street, Arbroath, enrolled at the then Dundee College of Art (subsequently Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art) in September 1933 on a four-year course leading to the award of the Diploma in Drawing and Painting. This was the start of a very successful artistic and academic period, and he made an immediate impact when he immersed himself in the social life of his fellow students. His academic record shows he gained a 1st class pass in “Illustration” and in “Illustrating Life” in each year of the course and was awarded a post-Diploma scholarship and also a grant of £60 for study in London or abroad in June 1938. This £60 was a substantial sum at that time, average annual pay in the UK that year being the equivalent of £208.60.

Hennessy’s main tutor at that time was James McIntosh Patrick R.S.A. (1907 – 1998, born in Dundee) who, in a letter to the author, said “I don’t know why the College Record uses the word “Illustration”. It was a “Painting” Diploma. I know you can now take a Diploma or Degree in “Illustration”, but not in 1938.”

McIntosh Patrick wrote of Hennessy:

“I recall him as a very brilliant student with a great deal of facility, able to produce rather highly finished canvasses very quickly and with a great deal of inventiveness. Even though it was fifty years ago, I can recall him only because he was outstanding.”

Another aspect of Hennessy was his love of theatre and ballet. McIntosh Patrick records “I recall when the Christmas revels (a dance for students and friends) came round, he produced some delightful ballets, something new for the students” and this love of music, theatre and dance remained with Patrick Hennessy throughout his life.

James McIntosh Patrick had a very successful career as a painter. In fact, he has been described as “probably the finest landscape painter living in Scotland today” by Lord Provost Thomas Mitchell on the occasion of McIntosh Patrick’s 80th birthday. His paintings are widely available in the form of colour reproductions and it is stated every second ex-patriot Dundonian probably has a print of his famous “Tay Bridge from my Studio Window”.

His paintings were popular with the (British) Royal Family of which many members own pictures by McIntosh Patrick. He was a member of the Royal Scottish Academy and he exhibited regularly in the Royal Academy London. His work became known to millions when a Mr. Frank Pick, Vice-Chairman of London Passenger Transport Board asked him to design a number of posters for London Transport. This was in the 1930s when he had employment as a tutor in Dundee College of Art.

If one is to draw conclusions as to the influence of McIntosh Patrick on Hennessy, love of landscape would be primary. McIntosh Patrick, in his impressive endorsement of Hennessy, probably saw something of himself in his pupil. Another tutor was Edward Baird (1904 – 1949) who became a successful painter in his own right.

Other painters whom Hennessy admired were Piero della Francesca and Vermeer. He felt that these two artists could engender emotion in the observer through painting stillness and tranquillity. It could be argued that Hennessy succeeded in this aim with his own paintings.

James Cowie (1886 – 1956), the well-known and respected Scottish painter who subsequently became Warden of Hospitalfield, was an influence on McIntosh Patrick’s figurative work. They got to know each other well but neither of them could have foreseen that ultimately Cowie would become Hennessy’s nemesis!

To return to Hennessy’s love of music and dance, one of the ballets he produced was set in Egypt. He helped design the costumes and the set and Hennessy himself, stripped to the waist and covered in gold paint, played the Pharaoh. The music that accompanied the ballet was Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries”. This production was so successful that it appeared again in the Kings Theatre, Dundee for a students’ charity show and was apparently very well received. The Patrick Hennessy of these years – extroverted, clever, erudite, was in sharp contrast to the introverted, reserved persona adopted in later years in Ireland. McIntosh Patrick’s recollection of Hennessy’s production of ballets also portrays a Hennessy who was one of the leading students when it came to the social and extra-curricular activities of his peers.

A fellow-student at that period, Leslie P. Harris noted “At College, he was quite a character and I do not remember him as a particularly private person, at times the opposite, but I understand from someone I met a good while ago that he appeared to have changed a bit.” The character that Patrick Hennessy displayed in College not only applied to his theatrical gifts but he also displayed an impish sense of humour. To quote Leslie Harris again “During his post-Diploma year, he sat and painted for some time in a corridor at the top of the stairs in full view of everyone. And there he painted a picture of three or four men sitting outside a country pub – one of the men with a large glass was Francis Cooper, the Principal of the College. Poor Francis was well aware of the picture and Pat used to hide it every weekend in case it strangely disappeared. Another jape he played on Principal Cooper was when he sawed off the locks on the lockers Cooper had just locked.” In one of the more elaborate pranks, Leslie Harris says “He got a lass to write a note ‘for God’s sake help, I’m being murdered’. The note was thrown out of a window and landed in Ireland’s Lane. Well, someone picked it up and took it to the police who had to follow it up. And they eventually arrived in the classroom. All, including Pat, were suspended from College for a week or so.”

These episodes illustrate another strand of Hennessy’s student life, mainly his dislike of and rebellious attitude towards authority, with the Principal, Francis Cooper bearing the brunt of the Dundee days. Henry (Harry) Robertson Craig (1916 – 1984), Hennessy’s fellow student and lifelong partner, recounted “That little girl Bonnie McKenzie is doing a composition with a sideboard and Cooper had just given her advice – See that your sideboard is in good taste, Miss McKenzie. Don’t paint one of those ugly Victorian pieces that Hennessy was always doing last year.” Obviously there was no love lost between Francis Cooper and Hennessy.

In a letter to Harry Robertson Craig, Hennessy wrote “I never look back at that dreadful College, God forbid, and I never want to hear of Dundee again, of Principal Cooper, Cowie, Mr. Day, Bannockburn and – I ran out of breath here”.

The subsequent inclusion of some of Hennessy’s works at an exhibition in Arbroath in 1938 consolidated his position as the leading graduate that year. After accepting his annual prize and embarking on his Travelling Scholarship, Hennessy visited London, Paris, Avignon, Rome, Florence. Craig mentions Hennessy received a commission from a Frenchman to paint a portrait while he was there.

During Hennessy’s time in Paris, Craig recorded that he visited the studio of Fernand Leger, but he subsequently had little to say about it. It was not unusual for leading artists of the day to open their studios to students, but there was no mention by Hennessy of further visits. He spent time in Galleries and Museums in every city he visited. He was a well-prepared graduate when he returned to Arbroath in the spring of 1939, ready to continue and finalise his academic training at Hospitalfield Post-Graduate College, which accepted students recommended by the four main art colleges in Scotland for three months during the summer.

At this stage of his life Hennessy was beginning to find life in Scotland, and Scotland generally, wearing. Exposure to the less restrained continental attitude towards life on his scholarship trip drew the comment: “After I escaped to the Continent for one period, I don’t think I could ever live in Scotland again – the grey streets, the landscape washed over with a sober Presbyterianism.”

It can be difficult to identify and come to a conclusion about his growing dissatisfaction with Scotland. He was the most successful student of his time at College. He was indulged and supported by his family who were rightly proud of him. But his life in Dundee is not remembered by him as a particularly happy time. Certainly in his correspondence in later years with Craig, he does not hold back: “On the rare occasions that you mention the names of the people who graduated with us, I have the greatest difficulty in trying to remember who they were, and at the same time a sense of dim horror that I should be tempted to look back down the unhappy perspective of my life in Scotland.” This rejection of what to the observer appeared to be a happy and successful conclusion to his academic life is puzzling. His later exploits at Hospitalfield were a continuation of this unhappiness and the culmination of his life in Scotland.

Hennessy did not receive a scholarship from Hospitalfield directly. He had applied and received a grant from Arbroath Town Council, apparently a unique event. There was a lot of class distinction within Arbroath. The relative poverty and humble address of Patrick Hennessy was not deemed the best place from which to be an artist. But his attendance at Arbroath High School and sponsorship by Patrick Ingles, coupled with his huge success at Dundee College of Art could not be ignored.

The Hospitalfield Experience

Hospitalfield House is an arts centre and historic house in Arbroath, Angus, Scotland regarded as “one of the finest country houses in Scotland”. It is believed to be “Scotland’s first school of fine art” and the first art college in Britain. In the mid-19th century Hospitalfield House was expanded by the owner, Patrick Allan-Fraser, a patron of the arts and bequeathed “for the promotion of Education in the Arts” on his death in 1890.

Patrick Hennessy’s attendance at Hospitalfield coincided with the appointment of James Cowie (1886 – 1956) as Warden in 1938. Cowie was by reputation a highly influential if rather dogmatic teacher. His work was noted for its meticulous draughtsmanship and strong linear style, and based on many preparatory drawings and studies of the Old Masters. His style ensured that he was among the most individual Scottish painters of the 1920s and 1930s. He was formerly Head of Painting at Gray’s School of Art. As Warden of Hospitalfield, his personality and dogmatism were likely to be in conflict with the young Patrick Hennessy, whose attitude to authority was well illustrated by his history at Dundee College of Art and his subsequent exploits at Hospitalfield.

The Minute Book in Hospitalfield for 1939, on page 143, noted the attendance of three graduates from Dundee College of Art – Alexander Allan, Harry Keay and Patrick Hennessy. The next entry is revealing and couched in beautifully restrained language:

“The production of the solid work of the session, moreover, was impaired by the extraordinary attitude of Mr. Patrick Hennessy after that (sic) results of the Carnegie Scholarship Competition (in which he had been unsuccessful) were known – to do as much harm to the place as one could, attempting to influence others to his point of view and taking (sic) at table with a studied impudence not to be believed except by those that have experienced it, an attitude which reached a climate (sic) when he felt he had the right to introduce to the house and table anyone he pleased. This remarkable assumption produced such tension that he came and said that the situation as between him and the management of this place had become impossible and that he was leaving. I agreed that the situation was impossible and he left. This was in the second week in August. The student I believe behaved in this spirit under the authority of Dundee College of Art.”

August 1939 ended Hennessy’s scholarship at Hospitalfield. Taking into consideration that the next month Hennessy was on his way to Ireland, I am confident that leaving Hospitalfield and Scotland was planned and his subsequent success and rapid assimilation into the Irish art scene was not accidental.

As a footnote to his Hospitalfield history, the extract below is worth noting:

The Hospitalfield Minute Book for 1939, page 144, states “he felt he had the right to introduce to the house and table anyone he pleased”. One can only wonder at the type or attitudes of the people he had introduced to Hospitalfield that so incensed Cowie. It is likely that as a native of Arbroath Hennessy would have met Robert MacBryde (from Maybole, South Ayrshire) and Robert Colquhoun (from Kilmarnock) at Hospitalfield in 1938 as there were many unofficial comings and goings of artist friends there. In the book by Robert Bristow “The Two Roberts”, he describes them re-connecting with Hennessy during their travels in Europe, so a friendship developed via the Hospitalfield connection and later extended to Hennessy’s invitation to visit him in Ireland after the War. Perhaps a personality clash with Cowie (who was not easy to get on with) was inevitable and it seems Hennessy was not exactly distraught at leaving Hospitalfield. After all, he left of his own volition.

Arrival in Ireland

Hennessy’s decision to return to Ireland was a brave one, probably motivated by his dislike for life in Scotland and a desire to conquer pastures new in his native land. He carried with him personal aspects of his life which he was determined to conceal and it is a remarkable fact that he was largely successful in doing so for all of his life in Ireland.

First, Hennessy never made others aware of his family background. His father’s membership of the British Army and his step-father’s role in the R.I.C. were a source of potential embarrassment.

Second, he was not forthcoming about the relatively humble origins of his early years in Scotland, which could in fact have been seen as an asset in Republican Ireland. His rise in artistic society from a poor background could have been a badge of merit, but Patrick Hennessy’s snobbery was a dominant factor and he kept any discussion about his Scottish family to the minimum. The never-changing text to an item about Patrick Hennessy was: Patrick Hennessy was born in Cork in 1915. The family moved to Scotland when he was at an early age.

Hennessy was well aware of these dangers to his image, so the culture of secrecy about these strands of his life became paramount. But the Hospitalfield incident and his attendance there was rarely mentioned and only became common knowledge after his death, and his manner of leaving Hospitalfield never became known in Ireland until now.

The arrival in Dublin in the year 1939 of a 24-year-old Cork-born Scottish-trained professional artist did not make the headlines. The sounds of war were beginning to be heard in Europe, but the arrival of Patrick Hennessy on the shores of Ireland was not the act of an objector or draft dodger. The various pieces of legislation introduced by Minister Kenneth Clark (later Lord Clark of the television series “Civilisation”) would have ensured that Patrick Hennessy would never have served as a front line soldier. The legislation made use of artistic skills in other ways, like camouflage, forgery of documents, map-making as well as appointing official war artists as had happened the case in World War I. It should also be noted that in the Dundee College of Art, the drawing syllabus contained a course on technical drawing, a skill that would not be lost in a wartime situation. On health grounds alone, Hennessy would not have been accepted into the military as he suffered from pulmonary problems that recurred all his life.

Ireland in the late 1930s was in a chronic economic position. The country was slowly shaking off the dead hand of the effects of Taoiseach Éamon De Valera’s disastrous economic war with Britain. But the looming European conflict was adding uncertainty to the financial and political future. Politically, neutrality was decided and the wonderfully titled “Emergency” was declared, to the annoyance of our nearest neighbour. Financially, the economy remained static and supply shortages led to the introduction of rationing.

As any study of the life and times of an artist cannot ignore the social, economic and political milieu surrounding him, this was the Ireland to which Patrick Hennessy returned to make a living as a full time professional artist.

One fact totally unexplained is the meteoric rise of Patrick Hennessy on his arrival in Dublin. The ease with which he rapidly inserted himself into the Irish artistic world was splendid from the point of view of Dundee College of Art and the subsequent travelling scholarship. While it is unknown if he ever returned to his native Cork as a schoolboy or student, it is unlikely. No mention appears anywhere of Irish visits. However, one possibility was recounted by Hennessy’s niece, Lily Lister. During his time in Arbroath High School he became very friendly with Meeda Ingles, the daughter of his art teacher. Meeda left Arbroath for Dublin in August 1939 and it is believed that Patrick followed her over. Meeda, however, joined the Society of the Sacred Heart, an order of nuns in Dublin, and no further contact ensued.

It may have been coincidence and it probably was, but Hennessy’s return to Ireland and his instant acceptance by the Irish artistic community and Dublin society has more than an element of chance and probably was the result of careful planning by him and unknown others. In mid-December 1939 a solo exhibition of his work took place in the Country Shop, St. Stephen’s Green, opened by no less a person than Miss Mainie Jellett (1897 – 1944). The number of paintings required for a solo exhibition leads to the assumption that he brought paintings with him.

Mainie Jellett was the predominant figure in the modern movement in Ireland, and was viewed as avant garde by the Irish public. For her to open the Hennessy exhibition, introducing an artist who was a total newcomer to the Irish scene, supposes that they knew each other or that she saw in Hennessy a potential that would enhance the Irish art world. It is possible that they met in Glasgow at the Empire Exhibition in 1938, where Mainie Jellett painted two large murals for the Irish Pavilion. Hennessy finished his Diploma course that year and perhaps through artistic connections (McIntosh Patrick or his tutors at Dundee) contact was made and for Hennessy, it was a tremendous beginning to his Irish career.

The solo exhibition included five portraits painted in Ireland, among which were a study of Madame Jammett, wife of the proprietor of Dublin’s famous French restaurant; a self-portrait; and two portraits of the children of the German Envoy to Ireland for the period 1937 – 1945, Dr. Eduard Hempel. This represented a prodigious output from mid-September to mid-December. J. McIntosh Patrick, in his letter to the author, recalled Hennessy “as a very brilliant student with a great deal of facility, able to produce highly finished canvasses very quickly, with a good deal of inventiveness.” These gifts obviously served Hennessy well in the assembly of his first Irish exhibition.

The portraits of Liv and Berthold Hempel are charming studies of the innocence of childhood. The children are in the garden of the official residence of the German Minister, Gortleitragh, on Sloperton Road, Dun Laoghaire, with the house in the background. Liv is holding a daisy in her childish hand, looking calmly, perhaps a little wistfully. The house was damaged in 1950 in what was believed to be an arson attack. The portraits of the Hempel children went back to Germany, together with the portraits of the Minister and his wife. But the portrait of Liv was returned to Ireland in 2011 and was sold in Dublin. The provenance was verified by Liv Hempel herself who now lives in the USA.

Hennessy also painted the Minister and his wife Eva. In a letter to Craig he states “The Minister’s wife has recommended me to do her portrait again, this time being mysterious in a cloth of gold in a twilight avenue. I am looking forward to this as she has a long-boned elegant face and beautiful arms and one rarely finds a sitter capable of collaboration.”

Hennessy’s first solo exhibition in Dublin also included landscapes and still lifes. Quoting the critic in the Irish Press. “His is one of the most interesting of the modern collections to appear here and embodies a union of the modern and mediaeval modes.” This conclusion is reached by the critic singling out certain paintings and noticing Hennessy’s impressive range of moods and techniques. This perceptive comment on Hennessy’s early work is the beginning of a lifelong belief by the critics that Hennessy was a bridge or link between modernism and the past, a stance that frustrated their ability to place his work in a labelled slot.

The Contemporary Painting Scene

In the 1940s the Irish artistic establishment, spearheaded by the Royal Hibernian Academy, was a mirror image of its London equivalent, the Royal Academy, firmly fixed in the orthodox tradition, untouched by the constant stylistic changes sweeping across Europe and America in the mid-20th century. This was beginning to cause unrest as it was perceived that the Academy artists were shutting themselves away from outside influences. The Short History of the R.H.A., in the Index of Exhibitors, draws attention to this: “An insular tendency had crept into the Academy since independence and the Annual Exhibition was subject to criticism for not showing identifiable national characteristics. This was answered by the artists who took a new look at the landscape and people in the more remote and rural parts of the island and became a dominant feature of the annual exhibition.”

It could be argued that the schools attached to these institutions perpetuated this tradition. Some graduates used the skills which put to good effect in the new artistic styles the basic fundamentals of drawing and painting taught in the Academies. Artists returning to Ireland from living or studying abroad, who had been exposed to these modern movements, found it difficult to survive. Commercial galleries were few and their stock in trade was traditional and familiar to the Irish buying public. Without being cynical about the likes and dislikes of the buying public, a hazy romanticised idea of an Ireland of idealistic landscapes, neat white thatched cottages, pretty colourful boats in tranquil harbours and Aran Islanders ad nauseam was the norm in taste.

Ireland’s position at the edge of Europe as a newly founded state, poor, subject to mass emigration and authoritarian religious domination, was a solitary one during the war and was not conducive to change or the new. Leaders of modern movements in art like Mainie Jellett, Norah McGuinness (1901 – 1980), Evie Hone (1894 – 1955), Louis le Brocquy (1916 – 2012) – who all had paintings refused by the Royal Hibernian Academy – had studied abroad and found their position isolated initially, but slowly things were changing. Societies like the Dublin Painters, founded by the artists themselves, the Contemporary Picture Galleries founded in 1939 and, probably of most importance, the Irish Exhibition of Living Art, first held in September 1943, were instrumental in introducing Irish patrons and public to modern artistic movements. The list of leaders of the new movement reads like a who’s who of the intelligentsia of Irish artistic society and the organising committee included Jellett, McGuinness and Le Brocquy. This new movement did not refuse works by members of the Hibernian Academy, but was an all-embracing liberal body showcasing the full spectrum of academic and modern Irish art. The academicians responded with grace and gave it support by patronage and membership.

Patrick Hennessy slotted neatly into both groupings, active in the Dublin Painters and exhibiting annually in the Royal Hibernian Academy. He appeared to have had little difficulty with the senior members of the Academy and particularly with Sean Keating, elected President in 1949. Dr. Eimear O’Connor references Keating’s personal notes in which he mentions frequently meeting Hennessy and urging the Haverty Trust to purchase works by him. In 1945 the Haverty Trust purchased two paintings by Hennessy, Exiles donated to the Municipal Gallery Dublin and The House in the Wood to University College Galway. Patrick Hennessy, while showing with Victor Waddington, did not have a deep or trusting relationship with him.

A few commercial gallery owners like Waddington and Leo Smith were outlets for contemporary artists to show their work, and when Waddington opened his gallery in London after the war, he continued to represent Irish artists there. In 1948, Hennessy was elected an Associate of the RHA. He exhibited 30 paintings at Waddington’s Gallery at South Anne Street and it appears to have been successful. However, it was Hennessy’s first and last solo exhibition at that gallery before Waddington left the Irish scene.

This was the Ireland Hennessy had returned to, but with confidence and accomplishment he overcame the challenges it presented. He established himself quickly and embarked on a life in a country and environment of his own choosing, with rewarding results both artistic and financial.

Fellow Artists, Ireland and the 1940s

The most telling way to assess Patrick Hennessy’s opinion of the Irish artistic world and Irish artists in general is through his correspondence with his life-long partner and fellow artist, Henry Robertson Craig. His pertinent, witty and often caustic comments are the best record we have as he was careful and restrained in face to face situations. While reading these comments, one has to keep in mind Hennessy’s love of language and his ability to use it for dramatic, theatrical effect, stretching his imagination.

The Royal Hibernian Academy was an easy target and his sarcastic comments contained some unpalatable truth. But at the same time as he mentions that “I should be humiliated indeed if I were reduced to putting A.R.H.A. after my name in a catalogue” he was pleased to accept the award in 1948 and to become a Royal Hibernian Academician one year later, proposed by Beatrice, Lady Glenavy, less than 10 years after his arrival in Ireland and aged only 34, a measure of his talents. His observations, like the following, are comic and he writes for effect, describing the scene for Craig.

“We have two main schools (Kindergarten) of painting here. The official, led by the President of the Hibernian Academy (Dermod O’Brien (1865 – 1945), has all the fervour and technical accomplishments of the Dundee Arts Society. A few of the members of the Academy do their best to push Orpen’s halo straight again and one or two of the youngsters (sic) rhapsodise over the Irish landscape but unfortunately with a Provencal accent. Their annual exhibition opens a week after Burlington House – unhappily the pictures are a decade later still, but nobody minds much.”

Fr. Jack Hanlon (1913 – 1968) seems to have had a fascination for Hennessy. He tells Craig:

“Then we have a little priest who took a few lessons from Matisse. When he told me I gazed at him with great interest, as I was convinced that the Almighty would reduce him to ash before my eyes. But He didn’t so I suppose I have a natural bent for cynicism and must accept the fact. At any rate our little Reverend does oils and watercolours in a manner curious to behold and sells them like the indulgences of a less civilized age. In fact, they are torn from his easel by the enthusiastic faithful.”

He apparently cannot get Jack Hanlon out of his mind. They seem to have had at least a friendly relationship. In 1948, Hennessy wrote: “The other day the little priest, Fr. Jack Hanlon, told me he is giving an exhibition of his paintings in the Wildenstein Gallery – you may remember the blue and yellow frenchified Madonnas.” Perhaps he was jealous of Hanlon’s London exhibition at such a prestigious gallery.

Hennessy appears to have been all things to all men, accepted as Academy material and in parallel viewed as modern. A slight hint of some dissent at his dual role is contained in the comment to Craig below, but if it relates to the Dublin Painters he obviously overcame it as he was eventually elected President of the Group in 1954, and re-elected for the following three years.

“I get a great deal of fun out of my back water watching the others conforming to their varied ideas of what an artist should be, the Exclusives or Private Means set modelling themselves on Whistler with an eye to Picasso’s latest experiment. They are stridently intelligent and their accent both in voice and paint would do credit to pre-war Bloomsbury. They are also careful to toss up an incipient Clive Bell or two and have seeped into our one cultivated monthly. By one of those miscalculations which even the sharpest make at times, they welcomed me into their Society when I landed in Dublin which means that I have been able to by-pass the dealers and run my exhibitions at cost price and no commission to hand out. They tried to dislodge me when they discovered – and very soon at that – that I had no talent for being a decorative adjunct to their parties, and found out that not only was I a painter, but worse still, I was no gentleman – so I stayed in the récherché nest, a vulgar cuckoo’s egg among the delicate blue wrens.”

Hennessy had what could be described as a grudging admiration for Jack Yeats (1871 – 1957), calling him “our Greatest Maestro”. From Hennessy, this was an affirmation of Jack Yeats’s position. He may not have admired Yeats’s technique, draughtsmanship or composition, but he certainly bit his tongue in his description to Craig:

“ …. Our greatest Maestro is of course old Jack B. Yeats. Don’t ask me to describe his work for I cannot. If large lumps of paint hacked and splashed on a canvas with no attempt at draughtsmanship or formal arrangement can be termed art, Old Jack B. is on a pedestal of his own. Think of Montecelli and Mancini with their hair down running mad with a new consignment of colours and you will have a hazy conception of Mr. Yeats’s larger epic. His small canvases have a mild flavouring of nostalgia but he is worshipped in this old town. Cezanne laid his first brick in the temple of modern art and Old Jack B. Yeats climbed heavily up the ladder and raised his trumpet on the spire. You will forgive a certain acidity in my description but when I point out that I have lived with them for over two years, you will see my justification. However, it cuts two ways. This enforced proximity, and my tongue which was never of the mildest has developed a delicate edge since my return to the land of Saints and Scholars.”

If Hennessy was at all critical of the Academy, it may have been an unenthusiastic attitude to it, but he reserved the full lash of his tongue for a certain group of artists who came to Ireland at approximately the same time as himself. As he saw himself as the bright new face of Irish art, he had little time for what he perceived as a more liberated free eclectic movement where ideas came from a variety of sources that they called Subjective Art. His comments to Craig about the arrival in Ireland of Basil Rákóczi (1908 – 1979) and Kenneth Hall (1913 – 1946) and their followers were particularly acid:

“The Moderns are quite another matter. Since the war a group of long-haired, velvet-breeched young intellectuals of all sexes arrived and started a movement called the “White Stags”. They paint (not alone on canvas), write, lecture and, God knows how! eat in the rare intervals of a vigorous pursuit of their startled muse. Dada has come to town and is being cut by Provincial Society. But they are tireless: exhibition follows exhibition, evenings of high philosophy and lectures on the simplest solution of the sex question provide us with a constant and cheap supply of entertainment, and if the public gatherings are not to your taste, Mr. Basil Rákóczi will initiate you into the ecstasies of yogi or the more humdrum excitements of psychoanalysis.”

“Mr. B.R. is apparently the founder of the society which was hatched out under the maternal wing of Lucy Wertheim in London and moved over to Dublin at the outbreak of the war.” (Lucy Wertheim was a prominent London art dealer.)“I am on distantly bowing terms with the White Stags as in one of my infrequent merry moods I rechristened them the White Snags and the name stuck. Not content with that, I discovered that the glamorous Mr. Rákóczi rose to the surface of an Upper Tooting font with Benjamin Beaumont writ large on his person – but here again I feel that the infant must have emerged from the womb under an alias: and Basil throws a cold smile in my direction whenever we are tactless enough to appear in the same room.”

Hennessy was not strictly correct. Basil Ivan Rákóczi was the son of a Hungarian gypsy and a Cork-born girl who became an artist’s model in London where he was born in 1908. This marriage broke up. However, his mother married again an Englishman, a Mr. Beaumont. Apparently Basil signed his early paintings “Basil Beaumont” but later reverted to his father’s name, probably to add a more exotic touch to his image and his role as a leading light in the new science of creative psychology.

Basil Rákóczi and Kenneth Hall came to Ireland with a group of like-minded pacifists and carried the White Stag name that had existed in London since the 1930s. Where Hennessy was accurate was that they were tireless as a group and were very active on the cultural scene during the war. While many of the more modern painters in Ireland freely associated with the White Stag group, no record exists of Hennessy in that grouping. The White Stag group was influential in the early to mid-1940s, but Both Rákóczi and Hall returned to London when the War ended. Kenneth Hall suffered from depression and committed suicide shortly after his return. Basil Rákóczi moved to Paris in 1946.

The general opinion about Hennessy and his relationship with anyone who came in contact with him was that he was socially easy to meet and to talk to but with a certain reserve, which served him well in gaining patrons at the top level of Society. In the 1940s, when money and materials were in short supply, he worked hard at his craft and image and a great number of his landmark paintings came from this period, namely Exiles, De Profundis and Old Kinsale, creating the platform for his future success. The 1940s were crucial to his future and he had no option but to make a success of his life and art in Ireland. Going back to Scotland was never an option both out of pride and his distaste for life there.

After the war, Europe had opened up to American money, industry and influences. The insularity formerly portrayed by the United States was broken down by the number of Europeans who sought refuge there before and during the conflict particularly artists. The vast amount of military and administrative personnel from America on European soil brought the two populations even closer, creating a curiosity about life styles and culture.

As early as April 1947, Time magazine published a review of a Manhattan Gallery exhibiting the work of twelve Irish painters. These included Louis le Brocquy, Patrick Hennessy and Jack B. Yeats, who was described as the leader and veteran Impressionist. The theme was that the Irish artists had found their own styles during the war years, described as “When Neutral Ireland was left to stew in its own juices.” There was a particular reference to a Hennessy painting (which was illustrated) titled Cathedrals. This painting depicted a ruined, Gothic skeleton of a building stretching into the distance, similar in composition to De Profundis, and described as bathed in a silvery light. The writer noted it was the love of landscape and the misty Irish light of Dublin, Connemara and the midlands around Tullamore that distinguished the Irish artists from the European mainstream. This kind of publicity was important to Hennessy and cemented his position as an Irish artist of note and was of tremendous value with his later involvement in the USA and the Guildhall Gallery, Chicago.

The 40s for Hennessy were defined by his ability as a portrait painter, receiving commissions in both Dublin and Cork. His works were selected for acceptance by the R.H.A.; his successful annual showings at the Dublin Painters; and his election first as an Associate of the R.H.A. in 1948 and the next year a full member. Visits to England and France completed a decade of achievement.

Some of his paintings of this period are indicative of the shortage of materials during and after the war; painted on both surfaces or on coarse canvas of rough quality, utilising available material like sacking or wrapping cloth. The practice of painting on both sides of the canvas, apart from the economics, could be the result of a refused portrait commission. The reverse of De Profundis, a signature painting of Hennessy’s, painted 1944/45, has a full-length portrait of a beautiful woman on the reverse. Another painting seen by the author, a painting of the symbolic Chinese dogs, titled The Dogs of Fo, has a highly finished still-life on the reverse.

Framing was another problem. During the war, frames were constructed in many cases by the artists themselves, and second hand frames had considerable value. Hennessy mentions in a letter to Craig “Yesterday I bought a stretcher (the last, I was informed).” The absence of imported mouldings probably reduced the visual effect of many fine works. Hennessy was passionate about framing his paintings. The late Diane Tomlinson who was a framer in the Hendricks Gallery, in conversation with the author in April 1987, told me that Hennessy could spend hours choosing a frame, offering up to the painting moulding after moulding to get the effect he desired – not really a surprise when one studies his paintings and their meticulous attention to detail.

The end of the 1940s saw a more settled Europe and Ireland. The economic situation, while slow, was hopeful. The Cold War was always a threat but a more unified Europe was emerging. Ireland was still exporting people, but stability was returning and hope was on the horizon. Patrick Hennessy was well placed to seize the chance in an upturn, and on the personal level the arrival in Ireland in March 1946 of his fellow Dundee student and lifetime partner, Harry Robertson Craig, was of immense importance to them both.

The 1950s – the Established Painter

Hennessy’s success continued throughout the 1950s. He and Harry Craig had moved to a more permanent address in Dublin, a studio at 28 Herbert Place, while still spending the summer months in Cork. As a newly elected Academician, he exhibited 6 paintings in 1950 in the RHA Summer Exhibition, including No. 119 Proclamation of the Republic 1949 priced at £120, a considerable sum at the time. This was also one of few examples of a history painting in Hennessy’s oeuvre.

That same year saw his painting De Profundis selected to tour North America as part of an exhibition of Contemporary Irish Painting organised by the Cultural Relations Committee of Ireland. The exhibition was shown in Boston and the Canadian National Gallery, Ottawa. It was probably as a result of this travelling exhibition that American art critics and gallery owners started to investigate and look seriously at Irish contemporary art and artists. A painting by Patrick Hennessy The Oracle (a title he used a number of times) was the cover of “What’s New” for April 1950. It was accompanied by a review of the painting by Emily Genauer, the art critic for the New York Herald Tribune “A precisely painted seashell on a weathered wood surface, or a pair of antique sculptured heads, such as Patrick Hennessy, well-known contemporary Irish painter, included in this picture he calls “The Oracle” can symbolise concepts as abstract as memory or eternity or the passage of time.”

The critic is aware of what Hennessy is attempting and of the surreal effect of the choice of objects and their positioning, stating “Mr Hennessy has painted a picture of mood.” This review must have given Hennessy some satisfaction. His constant efforts to emulate the Dutch masters whom he admired, particularly Vermeer, was bearing fruit.In 1951 the Dublin Painters mounted a ten year retrospective titled Paintings 1941 – 1951, a retrospective by Patrick Hennessy RHA (with a Foreword by Sheila Pim). The 33 paintings were an exhibition of the full gamut of his artistic ability to address the huge range of subjects in which he excelled. Sheila Pim concludes her foreword by stating:

“As an Irish artist, Patrick Hennessy ranks among the most sensitive interpreters of our surroundings and human types, but his work should also be viewed in a wider context. The future is unpredictable but full of possibilities, for we are in the presence of an artist of integrity and insight, in full command of his technique.”

Hennessy continued to progress his career. He was now making a decent living and travelled to France, Switzerland and Italy in 1951, spending time painting the ruins and the rebuilding of the Monastery of Monte Cassino in Italy, the scene of a famous military engagement during WWII. His passion for stone is fully indulged in these paintings. The visit to Venice resulted in the painting The Bronze Horses of St. Mark’s.Once again, Hennessy had captured more than an image, but a mood. This atmospheric painting was bought by Major Stephen Vernon and exhibited at the Royal Academy London in 1955. In conversation with the author, Major Vernon quoted Sir Kenneth Clarke as saying about the Bronze Horses “In any country in any century, this would be viewed as a fine painting.”While in France, Hennessy visited Versailles and several paintings of the palace were produced. Hennessy’s travels were always fruitful and evident in his annual exhibitions.

Back in Ireland, Hennessy was welcomed into the drawing rooms of the rich and titled, particularly the remnants of the Anglo-Irish Establishment. He was attracted to titles and among the many patrons with whom he cultivated warm personal relationships were Major Stephen Vernon and his wife Lady Ursula Vernon. Lady Ursula was the eldest child of Hugh Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster and one of if not the richest man in Britain. Major Vernon was an officer in the Irish Guards but during the war was stricken by polio. This handicapped him for the rest of his life. Major Vernon had a strong interest in horses and the Duke of Westminster gave them charge of his stud farm in Bruree, Co. Limerick. The Major was successful at the stud farm, breeding “Hugh Lupus”, a winner of a Classic, the Irish 2,000 guineas. However, in 1959 the Vernons purchased Fairyfield, a charming Victorian residence overlooking Kinsale Harbour as a summer retreat.

Both Hennessy and Harry Craig were frequent visitors to Fairyfield and in 1961 Hennessy painted a substantial mural in the main drawing room with a profusion of roses framing the window, clinging to a classical arch. The artist signed his work Hennessy Pinxit. He became an established figure in social and diplomatic circles with invitations from the British Ambassador (1959 – 1964), Sir Ian MacLennan, to painting parties at the Embassy. The contact with the Vernons brought Hennessy and Craig into the company of the author Elizabeth Bowen, with visits to Bowen’s Court where they met many members of the literary set including Iris Murdoch and Evelyn Waugh. Hennessy painted Elizabeth Bowen at least three times, the most famous being his study of Bowen on the staircase at the window of Bowen’s Court, which is in the permanent collection of the Crawford Gallery, Cork, donated by Major Vernon.

Another source of revenue opened up for Hennessy. His ability to faithfully render architectural detail earned him commissions. He painted Bowen’s Court, Bruree House, and a number of other buildings including some in the North of Ireland – The Moorings, Beningan House and Windy Lodge, Lisburn, the residence of the Barbour family. Hennessy’s patrons were extremely loyal and some collected substantial quantities of his work. His list of clients includes a Who’s Who of Irish contemporary society: John Sisk and family, Major Stephen and Lady Ursula Vernon, Elizabeth Bowen, Gordon Lambert, the Goodbody family, the Cruess-Callaghans and Lavinia Reddin.

A significant event in the life of Hennessy during 1956 was the opening of the Richie Hendriks Gallery at No. 3, St. Stephen’s Green, by his friend David Hendriks in April of that year. Both Patrick Hennessy and Harry Robertson Craig had a major part to play in the founding and opening of the Gallery. The Jamaican born David Hendriks first visited Dublin in 1947. He returned to Ireland in 1950 to study Economics and Political Science at Trinity College. He had made a number of friends among the artistic community, including Barbara Warren, who was a member of the Dublin Painters of which Hennessy was Chairman and Craig a member. Barbara Warren introduced them to Hendriks and they became firm friends.David Hendriks continued to attend Trinity where he received a pass BA in Arts in 1955. He had a private income and was not under any pressure to return to Jamaica or embark on a commercial career.

The seeds were being sown in Hendriks’ mind to open a gallery. He knew Hennessy and Craig; Victor Waddington had closed down his Dublin gallery; and a commercial opportunity was opening up for a new gallery in Dublin. The influence of Hennessy and Craig was important and they were instrumental (with others) in convincing David Hendriks that the conditions for opening a commercial gallery were favourable. Hendriks seized the moment and set about searching for a suitable premises. Things fell into place as the first floor of the building occupied by the Centre for the Exhibition of Irish Goods at No. 3 St. Stephen’s Green was vacant and its Administrator felt the image of an art gallery was suitable for the Centre. Hendriks acquired a favourable lease and work started on preparing the space for a gallery.

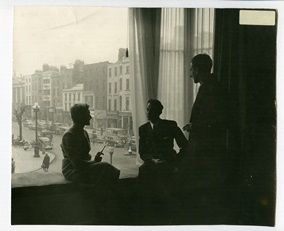

The window of the Hendriks Gallery, No. 3 St. Stephen’s Green Madame Simone Guinoseau, David Hendriks and Patrick Hennessy

Both Hennessy and Craig helped physically to refurbish the rooms in the gallery, which opened on 12th April, 1956.The importance of the Hendricks Gallery in the life of Patrick Hennessy could not be overestimated. It gave him the solidity of a sound commercial background and administration, with a solo exhibition annually and participation in group shows. As the international reputation of the Hendriks Gallery grew, contacts were made with the Guildhall Gallery, Chicago, to the benefit of both Hennessy and Craig. In that same year, 1956, they made the move to their final studio address in Dublin at 19 Raglan Lane, Ballsbridge.

The other major event in Hennessy’s artistic life was his solo exhibition in Thos. Agnew & Son, Bond Street, London, where he exhibited 38 paintings including the portraits of Elizabeth Bowen and Lady Ursula Vernon. This exposure to the London market led to several portrait commissions in London, including one from a Monsieur Imbs in Paris, where Hennessy undertook the commission in late October. Hennessy finished the decade with a major painting trip to the West of Ireland in 1957. Craig records that he “sells all the West of Ireland Paintings” at the Richie Hendriks show later that year where he exhibited 31 paintings. A successful decade with substantial rewards.

The 1960s – Life Changes

In late 1959 and early 1960s, Hennessy was beginning to show the onset of a period of ill health. He did not exhibit any paintings in the R.H.A. in 1960 and exhibited only one painting in the Oireachtas which he rarely failed to do. He and Craig drove through France to Spain early in that year, visiting Paris and Madrid, and saw Semana Santa (Holy Week) in Malaga and the Feria in Seville. They rented in a seaside village called “Los Boliches” (The Dragnets) and the results of the Spanish visit, as always, were recorded in the paintings in the annual Hendriks Exhibition. Hennessy’s love of theatre, costume and colour is given full rein with this subject matter. One of those paintings The Spanish Christ is now in the collection of the Ulster Museum.

The winter of 1961/62 was a difficult period for Hennessy. He was very ill and developed pleurisy, was brought to hospital and there were fears of Tuberculosis. He recovered slowly but was unable to produce enough work for his annual showing at the Richie Hendriks Gallery in 1962. For three consecutive winters Hennessy developed severe bouts of illness, of pleurisy and other pulmonary problems. His doctor, William George Fegan, who became a close personal friend and patron, suggested that Hennessy winter abroad in a warmer dryer climate. As a result of these increasing health challenges, Hennessy and Craig decided to winter in Tangier, Morocco in the future. They continued to spend winters abroad until 1970 when they made a more permanent move to Morocco.

From 1963 onwards, the content of Hennessy’s exhibitions began slowly to take on Moroccan themes. He expanded his repertoire of still lifes, embracing the rich textured fabrics of North Africa. His palette became lighter, reflecting the North African sun. The critical reviews about his technique and subject matter continued to be peevish. One review stated “There seems to be no middle-of-the-road reaction to Patrick Hennessy: either you like his work or you don’t. Personally I belong to the second class, though I can on occasion bring myself to appreciate his particular merits.” He goes on to say “No matter what reviews he gets, the man seems to sell.” The reviewer was right. Fortunately for Hennessy, this was not reflected in his sales. The art-buying public ignored the critics and his shows were usually very successful.

In 1964, David Hendriks moved his Gallery to 119 St. Stephen’s Green and in April the following year had the first exhibition in the new Gallery “Painting and Sculpture by Irish Artists”. While Patrick Hennessy did not exhibit at the R.H.A. that year, he maintained his position in Hendriks, showing 21 paintings in November. In 1966, he had his first exhibition at the Guildhall Gallery, Michigan Boulevard, Chicago. This contact had a huge effect on the lifestyle of both Hennessy and Craig. The exhibition was a great success and firm relationships were built with the personnel in the Guildhall; Konstantin Litras, Anne Schwarz and Rhoda Epstein. This Gallery was very professional in their dealings with Hennessy and Craig, producing brochures, programmes and promotional film. They also used top class framers like Heydenryk, a New York framer of Dutch origin. Heydenryk were chosen by the Guildhall because their high standards and original methods and materials helped sell their paintings and they were requested by their clients. At some point, either Hennessy or Craig may have suggested that the Guildhall order in stock sizes for their picture frames (most probably Craig – Hennessy was too particular about frames) as they painted on standard size board or canvas. Rhoda Epstein gave them the answer, in a letter dated 27 February 1969:

“As for frame ordering according to size, we just wouldn’t think of doing it that way, when either your or Patrick’s paintings come to the gallery they are like new children, with special attention given to the framing of each one, you’d never order twelve pair of shoes without first seeing that they fit!”

The Guildhall Gallery provided this sort of professional attention in all their dealings with Hennessy and Craig. By dealing with them in Morocco and not Ireland, the proceeds of their sales went straight into their Credit Suisse bank account in Zurich. These transactions began to build into substantial amounts of Swiss francs. By the end of 1969, Hennessy had forwarded either directly or via Hendriks nearly 200 paintings to the Guildhall Gallery. He was now beginning to sell more paintings abroad than in Ireland. At the same time, his sales through Hendricks had considerable value. A letter from Craig to the Guildhall Gallery on 7th January 1969 indicated:

“We finally got the full results of Patrick’s show with David in Dublin and it seems to have been the biggest money earner of any contemporary painter for years in Ireland.”

In 1968 Hennessy and Craig moved to a new location in Tangier – 16 Bonita, Rue Jean Jacques Rousseau. This apartment was owned by Lady Patricia Duckworth-King, who lived nearby on Ave Hassan 11. She apparently had a rose garden where Hennessy painted. In return, Lady Patricia received painting lessons from Patrick Hennessy, particularly roses. Lady Patricia became a close personal friend of both artists, so much so that she was a beneficiary in Craig’s Will, receiving £2,000 and a painting each by Hennessy and Craig.

When Hennessy returned to Dublin for the summer in April 1969, both he and Craig had decided to move to Tangier on a more permanent basis. For economic reasons it made a lot of sense. The Guildhall Gallery in Chicago was selling their paintings at a steady rate. The Irish market was performing well, usually selling out Hennessy’s winter show. With the advantage of a Swiss bank account for the American dollars and the added advantage of a warm, dry climate, Tangier was attractive to Hennessy, who suffered from pulmonary problems partially due to the fact that he was a very heavy smoker. They did not entirely burn their boats behind them. The 1969 Finance Act offering tax exemptions to artists was introduced by the then Minister for Finance, Charles J. Haughey, and it solved any tax liabilities they may have incurred in Ireland.

In 1970, they sold the studio in Raglan Lane to Hennessy’s doctor, George Fegan. Dr. Fegan’s children were at college in Dublin and required accommodation. Susan Mulhall, Dr. Fegan’s daughter, remembers the studio vividly. Both artists had left material, both finished and unfinished canvasses behind them, but they were never to return to Raglan Lane. Hennessy and Craig were known and well established in Morocco by then, so they settled down to a comfortable life doing what they liked doing best – painting.

Hennessy’s Last Decade

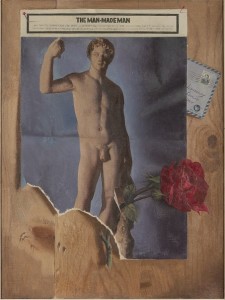

Back in Ireland the 70s began with the selection panel of the Rosc 71 “The Irish Imagination 1951 – 1971” choosing the Hennessy painting The Man made Man and Rose for their exhibition. This painting is the subject of an article by Brian O’Doherty in the Rosc catalogue titled “The Puritan Nude” which deals with Irish and British attitudes to the nude and Irish artists’ reluctance to paint it or ability to avoid it. The painting depicts a 16th century Florentine marble life size image of Jason and the Golden Fleece (the statue is currently in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

The image is portrayed on a magazine page pinned roughly to a timber plank, torn at the base, with a red rose projecting through the paper, the trompe l’oeil effect superbly rendered. A hand-written envelope protruding from behind the page is used as the vehicle for the signature of the artist and the stamp is a self-portrait. The irony of this painting is that the page is an advertisement for a medical company that manufactures prosthetics. The description of the statue in the Victoria and Albert Museum indicates: “The figure was extremely damaged and the principle losses have been made up in marble. The nose and two locks of hair over the forehead are modern.” Is Hennessy having a wry moment?

Early in the 1970s, David Hendriks was trying to develop a policy, namely to bring the Dublin Exhibition and Exhibitors to the various Arts societies and venues that existed in provincial towns. In 1974 he held a joint exhibition of Hennessy’s and Craig’s works at the headquarters of the Cork Arts Society at Lavitts Quay. Craig exhibited 20 paintings and Hennessy 13. This show was deemed to be a success and Hendriks followed it up later that year with a further show in November of a group of artists currently showing with him in Dublin, including Robert Ballagh (b.1943 – ), Patrick Collins (1911 – 1994), Barrie Cooke (1931 – 2014), T.P. Flanagan (1929 – 2011) and, of course, Hennessy and Craig, with three paintings each. The following year in The Exhibition of Irish Art 1900 – 1950 Rosc Cork, 1 December 1975 – 31 January 1976, three Hennessy paintings were exhibited, including No. 42 Kinsale Harbour, lent by the Limerick City Gallery of Art. This was the last exhibition in Cork before his death to show Patrick Hennessy paintings.

1975 was the year that the Guildhall Gallery celebrated their association with Patrick Hennessy with a 10 year retrospective exhibition. They pulled out all the stops with a full colour catalogue, taped interviews and a short promotional film. Hennessy was firmly on the map in the U.S.A. His sales were steady and, as in Ireland, certain loyal clients bought several of his paintings. His rose studies were extremely popular and his ability to render with precision these studies appealed to the Guildhall clients. Commercially Hennessy was important to the Guildhall with both parties benefiting greatly.

For the remainder of the decade Hennessy’s contact with Ireland declined. He had not been back to Ireland since 1977, three years before his death. However, he continued to forward to David Hendriks paintings for private sale. His last major exhibition with David Hendriks was in 1978, when he showed 31 paintings. Every year the R.H.A. received a quota, a recognition of the privilege Hennessy felt to be a member. Only in the year he died did he fail to submit a painting.

In one of his last letters from the Algarve, Portugal, dated 2nd May 1980, Hennessy wrote to his sister Brida (pet name, Christian name Mary, married name Craig), apologising for not writing as they had been on the move continually since leaving Morocco and this was a more settled address. He compared Portugal with Morocco as very like it but the great difference being they were now living in a country where there was some kind of law and order. He wrote:

“We were sad naturally at leaving Tangier which both Harry and I liked so much. But the last few years, and particularly since the appearance on the scene of that evil old man, the Ayatollah Khomeini, things started to deteriorate and, as far as we could see, would only get worse.”

He was obviously referring to the War in the Western Sahara, which was about the presence of the Spanish troops in the area. King Hassan II was attempting to get international recognition for his claims on the territory. He organised what became the Green March in November 1975 in which 350,000 Moroccan men and women crossed into and occupied the disputed region. This action led to a Spanish withdrawal. However, the indigenous tribes in the area created a guerrilla movement called the Polisario, supported at various times by Algeria and Libya and the issue became bogged down in a war of attrition at a constant cost to the Moroccan Exchequer. It ruined the economy of the country and the cost of the war drove up prices, coupled with announcements nearly every other day of new taxes.

In the letter cited above, Hennessy continued “We might have to face a crippling tax bill as has happened people we know. You pay or go to jail. The only other alternative is to leave everything you possess and then you are allowed to go”, which is what Hennessy and Craig did.

He finishes the letter on a contented note: “We are renting a pleasant little house, quiet, a few miles from Lagos, with a most paintable landscape all around with a lot of trees, and our nearest neighbour is at least half a mile away which suits us very well. So we intend to stay here indefinitely and may think of buying the house if we can reach a satisfactory figure with the people who own it.” He goes on to say “Harry and I came to Portugal last December to see what the country was like and for five weeks could almost have believed that it was summer all over again; cloudless skies, warm breezes, people sitting outside the cafés and in the parks in their summer clothes and in the garden of the house we rented there a variety of flowers in full bloom.”

Hennessy’s Demise

The Hennessy family were notified by a letter Harry Craig wrote on 3rd January 1981 to Brida Craig informing her of her brother’s death and giving her details of his funeral arrangements, namely “Tony (family name for Patrick) passed away on the 30th December 1980 and was buried yesterday, Friday, by Father Angus of Golders Green Cemetery, according to the rites of the Roman Catholic Church.” Apparently none of the Hennessy family was otherwise informed of his death. The fact that it happened over the New Year holiday, coupled with the intervention of a weekend, did not help communications and the letter to Brida Craig was the first notification of Hennessy’s demise. Harry Craig continued: “It all happened very suddenly and I was advised by Fr. Angus that if I delayed the ceremony it may have taken weeks owing to the public holidays and the enormous amount of people awaiting burial because of the cold winter, etc., so I advised him to do what was best.” Small comfort to the Hennessy family.

“He was immensely secretive, the most private person I’ve known. He shunned all publicity, seldom even showing up for his own openings (“I might put people off buying” he told Hendriks). But he lived only for painting” says Hendriks. “He never had any other work, not even lecturing. It was everything for him.” And finally “The most overlooked Irish artist of our time”, David Hendriks’ final words about his friend and colleague.

Hennessy’s Position in the Firmament of Irish Artists

When the history of Pictorial Art in Ireland in the 20th Century is written, some painters will merit particular mention. Some will be referenced for their ability to involve themselves in the mainstream of European Art Movements and adapting them in an Irish dimension. Others will be noted for their distinctive personal styles and creating their own stamp and personality on that set. The vast majority of artists will not merit a mention at all. Only the few who either change things and alter the public conception of art, or develop and establish a distinctive personal style will be remembered.

His technical virtuosity was of course his saving grace. He could paint and draw in a world that was being told that composition and craftsmanship were old fashioned virtues, and that abstraction, blurred imagery and colour could compensate for a lack of the basic skills. He ignored the popular call and continued to paint as he wanted. If there were any major changes to his work, they were a leaner palette and matt finish, coupled with lighter tones that were the consequence of the North African sun. Hennessy’s attitude toward the Contemporary Movement is best described in his own words:

“Today we are given a picture of life that claims to be a succession of dramatic innovations, not only of techniques, but of a conception of reality transcending the materials the painter is forced to use. Canvas and paints are no longer enough. The traditional methods go by the board. The artist takes what he finds at hand, experiments with plastics, cement, flashing lights, etc., and presents us with his brand new conception of twentieth century art. Up to a point we accept his findings as valid. But only up to a point. He has possibly extended the language of painting, but what in the long run has he told us that couldn’t have been said just as well with the vocabulary bequeathed to us by men of the stature of Rembrandt or Chardin?”

Bruce Arnold, in his Concise History of Irish Art, suggests that to some degree Hennessy bridged the gap between the Living Art and the R.H.A., a perceptive comment indeed.

David Hendriks said of Hennessy after his death “He wasn’t fashionable, wasn’t in the mainstream – and he refused to change.”In conclusion, perhaps the one person most qualified to make the final comment about Patrick Hennessy would be the late Harry Robertson Craig, who stated:

“I never ceased to admire his steadfast belief in the interpretation of the world and nature as he saw it and not as in the ever-changing fashions in the painting of that period.

“Now that taste is changing once more to representational art, I think that his importance in this field will be more and more appreciated.”

But that is for Art Historians to judge.

The Letter

Cork

Sat

My dear Alex,

You must have wondered why I have taken so long to reply to your letter, and, indeed I feel very guilty at the delay. I spent the winter in Northern Ireland where your letter was forwarded to me and several times I made an attempt to write but somehow I was invariably interrupted and have put it off until I had returned to Dublin. There of course you have as much chance for privacy as the celebrated goldfish and now as I am once more in Cork I have no further excuse for putting off what is really a great pleasure to me. I cannot explain why it is always so difficult to write to your friends (telephoning is another of my several neuroses, I am capable of letting weeks pass rather than lift the receiver and make an appointment with someone I am genuinely anxious to see that indeed I have lost many a sale on account of this odd behaviour but nothing will cure me now). I hope you got through the winter safely – Damn! I am on the point of meandering on with chitchat all evening. Sort of mood that comes on me occasionally, when I am capable of writing what looks like a rough copy of an Annie S. Swan masterpiece.

Thank God that the war in Europe is over. I am still half dazed to think that such a miracle could take place, that it is no longer an accepted convention that human beings should kill one another with such remarkable efficiency. It must’ve been particularly difficult for you as you have the courage to detach yourself from the sorry mess and yet had to live in that chaotic atmosphere. I often thought of you wondering how you were getting on, and hoping that the strain would not affect you too much. Hilda must have been a great help to you. Now, thank God once more, it is over and we can all start living our lives again.

The declaration of peace caused little interest here though a few silly students in Trinity College threw the patriots into a frenzy by burning the Irish flag. Bands of elderly ladies marched to and fro with banners and such like, and after a deal of speechifying burnt a home-made Union Jack. The inveterate pro–patriots and mothers-of-ten have been having a field day in the correspondence columns of the press; and I hear that the English papers have been banned in case our delicate nerves would be shocked by the Daily Mail’s screams of fury. I dare say you will have read about it by now. Poor sinister little Éire– the spy stories and tales of ruthless international organisations that occasionally one used come across, to my amusement were implicitly believed by the hard-headed Presbyterians in the North but gave rise to nothing but yawns here.

The latest rumour that Haw-Haw has bought a castle a few miles outside Cork and has already flown to Ireland is the latest topic of conversation. Indeed, a few diehard Nazi sympathisers are confidently expecting the arrival of the Führer and one mad creature is torn with indecision as she dare not wear mourning as it might imply a belief in British propaganda. But on the whole the war was accepted here as one accepts the weather. I knew aristocracy, the businessmen, doctors etc. were too busy making money and the others too busy trying to make ends meet to have a great deal of time over for philosophical reflection. The cost of living here has risen to three times its pre-war levels but mercifully the rich disgorged their small change on paintings among other portable investments and I was able to continue working. With the end of the war and the consequent stability on the stock exchanges, the volatile creatures may lose their new-found enthusiasm for ‘culture’ and stray back to Consolidate Brick etc. but I think that there is a genuine interest in painting here. There must be and one is not easily discouraged, if it can survive the amazing daubs that pass for current art in Dublin. Modern art – the use of the word Modern is good as the earnest little things in sandals in spectacles are still strenuously ‘understanding’ 1920s Picasso — that is all the rage in the advanced suburbs, and a few of the choice spirits are making tentative studies of bones and other modish bric-a-brac. Heigho! May they choke, the lot of them!

You will be amused to hear that our late friend Charlie Owen has popped up again, this time as a Corporal Owen one of the Éireann army. There was a long article in the Irish Shrine a pious little weekly devoted to keeping the faith bright – it was cut out and sent to me by an old lady who saw my name mentioned in connection with him as we were both alumni of the Dundee College of Art — which gave his life history including his somewhat ambiguous entrance into – and departure from an English monastery.

He had a picture of Ireland being neutral with a wealth of flags and sallow saints in the Academy last year and in this year’s exhibition Saint Patrick bearing a striking likeness to C. Owen, is decoratively fending off a Demon equipped with a handsome tail among other attributes of evil. I shuddered my way past the monstrosity and came face-to-face with the maestro who would have fallen in the bosom of his long lost friend had my face expressed anything but a polite blankness. I have long since learned the necessity of confining my interest to the few people I like. The others merely waste your time and interest and after seven or eight years I feel that I’m entitled to leave people like our Charles safely marooned in the past. And then his painting nauseated me, this pious clap-trap not one whit different from the rubbish he used to do in Dundee – if anything, worse! I never at any time had much affection to waste on my fellow painters with the exception of the friends I made like yourself and Harry; and bad painting irritates me like a personal affront. I cannot forgive it as it seems to be a reflection on what I consider the only form of activity of any value. The war has taught me that, at least. I am puzzled by the way people squander their energy and intelligence on things like politics, religion et cetera to say nothing of money making and the tribe of snobberies that give point to life but is scarcely worth the bother of living. When the artist starts to agitate for this and that, I throw my hands up in despair. As I well imagine it’s the birds’ duty to chirp a melody in the tree tops. But then I suppose it is easy for me to be detached in my neutral vacuum, having for the most part no propaganda to contend with. Here there was nothing to do but paint, and if you are foolish enough to be deflected from your own job you can blame nobody but yourself.

We were allowed the privilege of deciding for ourselves what sort of defeat we might care to choose. I dare say if I had stayed in Britain – and at moments I almost regret my rapid departure — I should not have had the courage to fight against our values and by now would be an energetic Communist [illeg]. Well then there was really no choice. There never is. Your character makes the decision for you, ignoring all head knowledge and the delightful mechanism of logic and rationality. They have their uses and very important ones, but I have come to the belief that your personality, or it may be your talent has its own method of defending itself, and drags your mind protesting from the battle that might demand too much of it. Again and again I have seen this happen in my own case and others.

Words, these damnable words that express so much and so little; I am inclined to think that Irish people have printers ink instead of blood in their veins.

Well I must stop as I have almost written myself out. I am becoming almost fond of Ireland now that I know that it will soon be possible to leave it. I have trained myself to the general belief in this country that there was nothing but space beyond the Great Wall of Éire and now that I know that I can return to … I stopped there trying to imagine what it is that I want to return to. But no matter, it will be different, and that will be enough.

Write soon and tell me how you are. And Hilda. I hope you have been working all this time. Give my regards to Broird [?] and my congratulations on his marriage. My friends McBryde and Colquhoun are full of an aesthetic-cum-revenanting zeal for the best interests of Scotland which rather saddened me as Éire has a way of dampening one’s enthusiasms for national cultures etc. However à chacun son dégoût.

Do you see Harry at all? He wrote some time ago telling me of Maggie Breun’s death. He didn’t say much but I should think it took a lot out of him. Poor Maggie had always the feeling about her – some vital spark was missing in her and she herself was aware of it and suffered from a sense of incompleteness. I was fond of her though. I’m afraid she didn’t altogether return the sentiment.

And now I really must stop. Perhaps we shall see each other again soon. I will spend the summer here as I have booked the gallery for my exhibition in November. After that, well, I simply cannot make up my mind at the moment, but I may possibly take wing again. I am still dazed by the good news of peace. Stalin or no Stalin.

Please give my kindest regards to Hilda.

Love,

Pat

Alexander Allan and his wife Hilda were contemporaries of Hennessy and Robertson-Craig at Dundee College of Art. The letter is undated but written in the early spring 1946.

Manuscript from a Private Collection.

Copy held in the Patrick Hennessy artist file, IMMA Collection.